- Folio No. 9

- About

- Feral Parrot : The Blog

- INTERVIEWS

- SUBMISSIONS

-

ISSUE ARCHIVE

- PRINT Chapbook No.6 Healing Arts

- Online Issue No.9

- Online Issue No.1 Fall 2016

- Online Issue No.2 Spring 2017

- ONLINE Issue No.3 Fall 2017

- PRINT Vol 72 No 2 Fall 2017

- PRINT Vol 73 No.1 Fall 2018

- ONLINE Issue No. 4 Fall 2018

- Online Issue No.5 Summer 2018

- FOLIO No.1 Fall 2018 VOTE

- ONLINE Issue No.6 Fall 2018 Fall Spirituality

- FOLIO 2 Fall 2019 Celebrating Dia De Los Muertos

- FOLIO No.3 -- Moon Moon Spring 2019

- FOLIO No.4 Celebrating New PCC Writers

- FOLIO No.5 City of Redemption

- FOLIO No.6 Spring 2020

- FOLIO No. 7 - Winter 2021 Into the Forest

- 2022 Handley Awards

- Inscape Alumni Board

- PRINT Chapbook No. 7 Healing Arts

- Blog

- Untitled

Cover Header Photograph by Marie C. Lecrivain c.Author 2019

FOLIO No.2 FALL 2019

INSCAPE MAGAZINE CELEBRATES DIA DE LOS MUERTOS!

Click to Learn About the Holiday and its Origins

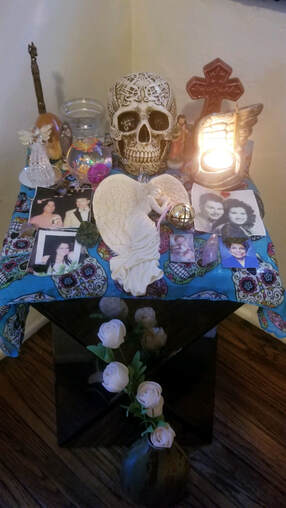

Ofrendas

Adrian Ernesto Cepeda - Beyond Sound . . . Envision

Anthony William Karambelas - That Which is Felt, Not Seen

July Westhale - Memorial Service

Divya Mehrish - Chewing on my Mouth

Thomas Price - The Krewe of Ghosts Rides Down Elysian Fields

Crystal Salas - We're Most Like Ghosts

Marie C. Lecrivain - La Santissima Muerte

Matt McGee - Every Day is Dia De Los Muertos When You're Irish

Cailey Thiessen - Ofrendas for a Country

Trudy Hale - Love Letter from an Ex-Wife

Samantha Simpson - The Last Judgment of Wanda

Jenny Patton - Candyman

Leanor Johansen - Love lives on

FOLIO No.2 FALL 2019

INSCAPE MAGAZINE CELEBRATES DIA DE LOS MUERTOS!

Adrian Ernesto Cepeda - Beyond Sound . . . Envision

“Death, our own sweet monster”—Alma Luz Villanueva

The radio signal keeps playing

over the sirens, Blackstar over

station to stations, spinning

the same, turning returning,

like mountains spewing--

explosions of epitaphs

once greeted souls through

speakers, cursing all through

strands of vulgar lava shadows

fire, flowing tempos of imminent

destruction, the heat once for tanning

under sun, is now evaporating skins;

melting our records resounding

“it’s too late to be hateful”

The California cannon

is here! Dark thought clouds over

our skeleton remains, no longer

need for rush speed induced diet,

those souls steaming flesh will

now feel skinny bone-like eternity.

Forget Zika viruses, invasions

from dark foreskin borders,

brothers homophobic

slithering in shadows

afraid of the sensual snake;

still shaking behind imaginary

walls, the dark clouds

of Xenophobic hate

have colored our valley

from Yellowstone where

the eruption first sang like

the loudest feedback bodies

could feel the Krakatoa

like detonation splinter

our once sunny California

sky. BMW car windows

splinters on traffic jammed

roadways, there is no escape

for all who shut off the hate,

the speakers that once crooned

saxophone Love Supreme now

trumpets our last call. Smoking

like babysitters who taught them, fuming

from all spurned created imagining

everyone else is to blame. As those

speak screaming outside

as dining room glass shatters

everyone’s familiar

remains, nature mocks

denialists complaints as ash winter

snows but never cools,

the seeds of these eruptions

come from absent mouths,

distracted mind and everything

along gluttonous fault lines, inciting

ones who whisper with other

tongues. But now a new language

of darkness breathes around

us. No one can breathe without

more hate, more blame. Fathers

once holy, still missing,

with distant right tinged radio

voices birthed this natural monster,

polluted more than our airwaves,

no more music, this disaster

more natural from the dirt

now spits on Mother Earth,

disgracing her daughters

while re-watching their second

coming on videotape, gifs,

filth tube that crowds railed

against, plays gripping

on repeat greeting the self-

hate deep love stoking, now taste

all the heat from stockpiles

of those riffles, Uzi’s bullet

hole arsenal can’t save anyone. Keep

shooting at mountains the lava

oozes still comes,

melting hyphenated last names,

skins once retouched

now fumes,

steaming to find divorcees

from reality cowering, as the volcano

has spoken burning pages from

the faith once forced all Sunday

Fox masses to regurgitate,

all the psalms still made up

will never cool the souls

sermons burned, there is no mistake,

darkness will shine, our time

has expired, nothing can stop

these end rhymes. Can anyone

feel the weather forecasting

all the fires forecasts distrusted

science now all dying disbelievers

unboxing our end times,

Southern man-made Pandora

has reopened destruction

monstering death

desecrates seething recycled

sermons once spoken from

venomous sponsors

of microphone reveals

estas dias de los muertos

everyone burning

internally, melting

our records, scales resounding

the California cannon appears

translating “it’s too late to be

hateful,” once gardening hopeful,

now reveals the slithering shadows

afraid of the sensual snake

cowering in disbelief,

all of those

who have serpent our fate.

The radio signal keeps playing

over the sirens, Blackstar over

station to stations, spinning

the same, turning returning,

like mountains spewing--

explosions of epitaphs

once greeted souls through

speakers, cursing all through

strands of vulgar lava shadows

fire, flowing tempos of imminent

destruction, the heat once for tanning

under sun, is now evaporating skins;

melting our records resounding

“it’s too late to be hateful”

The California cannon

is here! Dark thought clouds over

our skeleton remains, no longer

need for rush speed induced diet,

those souls steaming flesh will

now feel skinny bone-like eternity.

Forget Zika viruses, invasions

from dark foreskin borders,

brothers homophobic

slithering in shadows

afraid of the sensual snake;

still shaking behind imaginary

walls, the dark clouds

of Xenophobic hate

have colored our valley

from Yellowstone where

the eruption first sang like

the loudest feedback bodies

could feel the Krakatoa

like detonation splinter

our once sunny California

sky. BMW car windows

splinters on traffic jammed

roadways, there is no escape

for all who shut off the hate,

the speakers that once crooned

saxophone Love Supreme now

trumpets our last call. Smoking

like babysitters who taught them, fuming

from all spurned created imagining

everyone else is to blame. As those

speak screaming outside

as dining room glass shatters

everyone’s familiar

remains, nature mocks

denialists complaints as ash winter

snows but never cools,

the seeds of these eruptions

come from absent mouths,

distracted mind and everything

along gluttonous fault lines, inciting

ones who whisper with other

tongues. But now a new language

of darkness breathes around

us. No one can breathe without

more hate, more blame. Fathers

once holy, still missing,

with distant right tinged radio

voices birthed this natural monster,

polluted more than our airwaves,

no more music, this disaster

more natural from the dirt

now spits on Mother Earth,

disgracing her daughters

while re-watching their second

coming on videotape, gifs,

filth tube that crowds railed

against, plays gripping

on repeat greeting the self-

hate deep love stoking, now taste

all the heat from stockpiles

of those riffles, Uzi’s bullet

hole arsenal can’t save anyone. Keep

shooting at mountains the lava

oozes still comes,

melting hyphenated last names,

skins once retouched

now fumes,

steaming to find divorcees

from reality cowering, as the volcano

has spoken burning pages from

the faith once forced all Sunday

Fox masses to regurgitate,

all the psalms still made up

will never cool the souls

sermons burned, there is no mistake,

darkness will shine, our time

has expired, nothing can stop

these end rhymes. Can anyone

feel the weather forecasting

all the fires forecasts distrusted

science now all dying disbelievers

unboxing our end times,

Southern man-made Pandora

has reopened destruction

monstering death

desecrates seething recycled

sermons once spoken from

venomous sponsors

of microphone reveals

estas dias de los muertos

everyone burning

internally, melting

our records, scales resounding

the California cannon appears

translating “it’s too late to be

hateful,” once gardening hopeful,

now reveals the slithering shadows

afraid of the sensual snake

cowering in disbelief,

all of those

who have serpent our fate.

Adrian is an LA Poet who has a BA from the University of Texas at San Antonio and he is also a graduate of the MFA program at Antioch University in Los Angeles where he lives with his lovely wife and their adorably spoiled cat Woody Gold.

Anthony William Karambelas - That which is felt, not seen

Entering my room one is assaulted by the unabashed profusion of ephemera. When I tally its contents, I can chart the phases that have defined my frail existence like eighteen tea lights festooned along a parapet. There are the sonic screwdrivers—four in total, three plastic, one cool metal, all timey-wimey, wibbly wobbly, decommissioned oddities—on a dusty shelf. There is the small green lightsaber that once fit a Yoda-sized palm. Now, the light will often flash spasmodically and flicker before it winks out, the whirring sound effects playing on, solemn as a dirge. Above it, like a protective teepee, there is a navy-blue diploma cover from my middle school graduation, a cream-colored leaf wilting inside. Off to the right, one can take his or her pick of an all but complete Lego set, at least a dozen magnets, and a myriad of other breeds of scattered kitsch.

It’s hard to believe that, at one point in time, everything here meant everything to me. It’s tempting to think I could touch each object and it would all come back. What it felt like to hold for the first time. The surprise. The elation. The rush of sanguinity like a warm towel thrown over a soaking head. The visibility. Of being little again and looking at this big world with small eyes. Knowing that someone was watching over. Feeling, or maybe just seeing, that lightsaber, that Lego set, so steady to the touch, and comprehending—because here was hard proof—that I was loved. But they are all just objects now, crooked, cheapened and jaded with age.

My mom never liked bought gifts on her birthday. She said it was the things I made that meant the most. So every January I’d slap together a slideshow or a song and wonder what it was she saw in these gifts when all I’d ever known of love was that it came dressed in wrapping paper and satin ribbon. It’s an adult thing, I always thought, and she’s not crazy, just a mom. I thought if I tried hard enough, someday objects would start to look like semiotics, not significant in and of themselves, but gestures of something so strong it took a trained eye to detect. So beautiful that if I made the effort, I’d see thirteen years in a blink.

These thoughts take me back to an otherwise unremarkable Wednesday afternoon when the doldrums of first grade had reached a tortuous peak after little over a week in. My fingers thrummed against the laminate finish of my tiny desk, pudgy digits adopting lives of their own as they flew across the coloring project laid before me. The teacher loomed overhead, a fawning overseer, sometimes materializing in the periphery of my vision, letting out a breathy "ooh" or "aah” that tickled my earlobe and sent a cool current down to the drum.

Halfway through the hour, she called me to the examination room, a small chamber of storage space set off from the classroom. As I approached, my feet dragged against the carpet like a prisoner returning to his holding cell. Should be quick and painless, she said, as she directed my attention to the pockmarked wall. There were few tests in kindergarten, I had gathered, but the ones we did have were monumentally inane. Like this one: recite your home phone number. Problem was, I hadn’t bothered to ask Mom.

Her hard wavered expectantly over a chart, gold star flickering on an index finger; there was a row there that bore my name. Two above me, Sabrina seemed to be doing well. Ten golden stickers and counting. ‘Star’ student.

She let out an exasperated huff. Now, Anthony, she said, don't tell me you've forgotten.

Two scarlet roses bloomed on my cheeks in reply, frustration and embarrassment in proportionate doses. The glimmering star, so near my name, retreated into her manila folder, and as she led me out of the room, I turned one last disdainful eye to the chart.

Perhaps it was a keen sense of infantile vengeance that impelled me to recount this episode to my mom. She'd heard about my lunch-time conquests of the wasps that skulked around the sandbox (this was before we found out the hard way that I was allergic). She'd heard about my phobia of art class, all because it meant scaling down a demonic flight of stairs to a hellish basement. I made her furrow her brows as she thought back to her own elementary school days. In just one week, my first grade experience had seen more trials than hers had in a year. She wasn’t sure how to take this.

I droned on in the backseat, the words colliding discordantly and signifying nothing. All I could think about was why those wasps grew their stingers like pirate’s hooks and why the paints we lathered onto loose canvases still clung to the thin flesh around my fingernails after a week of washing? Why those ten digits were so important to remember when they could be found in the student directory and why the teachers made such a big deal of reciting them? So when I told my mom I wasn’t learning anything, I might’ve been hyperbolic because it wasn’t that I wasn’t learning anything, it was just that I wasn’t learning the right things. I sensed this with a certain inexplicable veracity, the type a mother might know from placing a cupped palm against her swollen belly and feeling a fuzzy peach head nuzzling against it.

At the next intersection my mom turned around in the driver's seat. She regarded me with a soft intelligence, the cogs turning in her inbuilt polygraph. My mother’s looks are, I think, deliberately enigmatic. They evince only three postures: concern, pride, and pain. So when she surveyed me, I could not see that her pale grey eyes burned with a cursed prescience.

As the light turned green and she settled back into her seat, she breathed deeply. Through the windshield, she saw her life mapped out like some terrible odyssey. Tomorrow, she knew she would withdraw her son from that school—never mind the $20,000 non-refundable tuition—and place him in another just a few miles away, where the classroom walls would be plastered with posters depicting the nine planets of the Milky Way and the forty-three American presidents. And when, by next August, his teacher gave him the same math test twice because she couldn’t possibly fathom how he’d gotten every answer right, his mother would pull him out again, purchase a new backpack and school supplies, and find him a small learning center on the third story of an office building thirty miles away. It didn’t matter how many times it took to find the right fit or how stiff her back felt in the early mornings or how the very vertebrae smarted like hot coals. Because when you love someone, everything else tunes out like white noise.

I was a little kid who loved his toys. I snuggled Bronco my plush horse and wound back toy cars on the spruce floor until video games caught my fancy. I quantified my life in objects because I thought it was all too messy and complicated to handle. I saw the things my mother gave me as sign of affection, but couldn’t comprehend that the beauty was not in the objects themselves, but the idea that she was watching. The idea that she listened. The idea that the things I have are just clutter, and when all’s said and done, they do just that.

It’s hard to believe that, at one point in time, everything here meant everything to me. It’s tempting to think I could touch each object and it would all come back. What it felt like to hold for the first time. The surprise. The elation. The rush of sanguinity like a warm towel thrown over a soaking head. The visibility. Of being little again and looking at this big world with small eyes. Knowing that someone was watching over. Feeling, or maybe just seeing, that lightsaber, that Lego set, so steady to the touch, and comprehending—because here was hard proof—that I was loved. But they are all just objects now, crooked, cheapened and jaded with age.

My mom never liked bought gifts on her birthday. She said it was the things I made that meant the most. So every January I’d slap together a slideshow or a song and wonder what it was she saw in these gifts when all I’d ever known of love was that it came dressed in wrapping paper and satin ribbon. It’s an adult thing, I always thought, and she’s not crazy, just a mom. I thought if I tried hard enough, someday objects would start to look like semiotics, not significant in and of themselves, but gestures of something so strong it took a trained eye to detect. So beautiful that if I made the effort, I’d see thirteen years in a blink.

These thoughts take me back to an otherwise unremarkable Wednesday afternoon when the doldrums of first grade had reached a tortuous peak after little over a week in. My fingers thrummed against the laminate finish of my tiny desk, pudgy digits adopting lives of their own as they flew across the coloring project laid before me. The teacher loomed overhead, a fawning overseer, sometimes materializing in the periphery of my vision, letting out a breathy "ooh" or "aah” that tickled my earlobe and sent a cool current down to the drum.

Halfway through the hour, she called me to the examination room, a small chamber of storage space set off from the classroom. As I approached, my feet dragged against the carpet like a prisoner returning to his holding cell. Should be quick and painless, she said, as she directed my attention to the pockmarked wall. There were few tests in kindergarten, I had gathered, but the ones we did have were monumentally inane. Like this one: recite your home phone number. Problem was, I hadn’t bothered to ask Mom.

Her hard wavered expectantly over a chart, gold star flickering on an index finger; there was a row there that bore my name. Two above me, Sabrina seemed to be doing well. Ten golden stickers and counting. ‘Star’ student.

She let out an exasperated huff. Now, Anthony, she said, don't tell me you've forgotten.

Two scarlet roses bloomed on my cheeks in reply, frustration and embarrassment in proportionate doses. The glimmering star, so near my name, retreated into her manila folder, and as she led me out of the room, I turned one last disdainful eye to the chart.

Perhaps it was a keen sense of infantile vengeance that impelled me to recount this episode to my mom. She'd heard about my lunch-time conquests of the wasps that skulked around the sandbox (this was before we found out the hard way that I was allergic). She'd heard about my phobia of art class, all because it meant scaling down a demonic flight of stairs to a hellish basement. I made her furrow her brows as she thought back to her own elementary school days. In just one week, my first grade experience had seen more trials than hers had in a year. She wasn’t sure how to take this.

I droned on in the backseat, the words colliding discordantly and signifying nothing. All I could think about was why those wasps grew their stingers like pirate’s hooks and why the paints we lathered onto loose canvases still clung to the thin flesh around my fingernails after a week of washing? Why those ten digits were so important to remember when they could be found in the student directory and why the teachers made such a big deal of reciting them? So when I told my mom I wasn’t learning anything, I might’ve been hyperbolic because it wasn’t that I wasn’t learning anything, it was just that I wasn’t learning the right things. I sensed this with a certain inexplicable veracity, the type a mother might know from placing a cupped palm against her swollen belly and feeling a fuzzy peach head nuzzling against it.

At the next intersection my mom turned around in the driver's seat. She regarded me with a soft intelligence, the cogs turning in her inbuilt polygraph. My mother’s looks are, I think, deliberately enigmatic. They evince only three postures: concern, pride, and pain. So when she surveyed me, I could not see that her pale grey eyes burned with a cursed prescience.

As the light turned green and she settled back into her seat, she breathed deeply. Through the windshield, she saw her life mapped out like some terrible odyssey. Tomorrow, she knew she would withdraw her son from that school—never mind the $20,000 non-refundable tuition—and place him in another just a few miles away, where the classroom walls would be plastered with posters depicting the nine planets of the Milky Way and the forty-three American presidents. And when, by next August, his teacher gave him the same math test twice because she couldn’t possibly fathom how he’d gotten every answer right, his mother would pull him out again, purchase a new backpack and school supplies, and find him a small learning center on the third story of an office building thirty miles away. It didn’t matter how many times it took to find the right fit or how stiff her back felt in the early mornings or how the very vertebrae smarted like hot coals. Because when you love someone, everything else tunes out like white noise.

I was a little kid who loved his toys. I snuggled Bronco my plush horse and wound back toy cars on the spruce floor until video games caught my fancy. I quantified my life in objects because I thought it was all too messy and complicated to handle. I saw the things my mother gave me as sign of affection, but couldn’t comprehend that the beauty was not in the objects themselves, but the idea that she was watching. The idea that she listened. The idea that the things I have are just clutter, and when all’s said and done, they do just that.

Anthony is a recent graduate of Cal State LA, where he obtained a B.A. in English (summa cum laude). He is an emerging writer, currently working on a memoir charting his path to college at fourteen, the motivations behind that decision, and the subsequent challenges he faced. Follow his work on social media. IG: @awkaramb Twitter: @supersyngnathid

July Westhale - Memorial Service

The plane touches the blistered face

of the tarmac, kiss kiss

and we’ve arrived. That’s it. It is

largely the same. In the eighties

my grandmother could kiss me

at the gate. She smelled of Virginia

Slims and Aqua Net, thought we could

get AIDS from a doorbell. That’s it.

If I didn’t like the conversation

my Walkman’s volume went up, up, up,

sang Selena’s swan song, gave me

grief about my hair and its flat desperation.

That’s it. It’s nothing

like before—the only exception:

the past still punches down,

which is a fate worse than doorbells.

The day my grandmother died

I ate green corn tamales, painted

my nails with her polish: Go Go Girl.

Kissed the petulant mirror

with my waterlogged face, knowing

there are larger castigations

for straying from memory

than duplication, but I do not know them.

July Westhale is a writer, educator, and adoptee. She was born in Arizona, but has lived largely in California, and has been in Oakland for the last ten years. She has her hand in many pots: teaching Creative Writing, working in reproductive health/patient advocacy, and writing to pay rent. She is the author of Trailer Trash from Kore Press. JulyWesthale.com

Divya Mehrish - Chewing on my Mouth

I am dissolving, teeth

grinding gasping tongue,

crushing blood. An itch

subdued but soreness

aches between lips. Charred

metal ringing like a church

bell against gums. I feel

good. Self-destruction

trickles down my spine

and makes me cold

at night. But I dream

about warming my body,

holding fur to stinging steel

and waiting for the heat

to diffuse. I lather myself

in the juxtaposition of fresh

and burn. I will wait until

my body reaches equilibrium,

until I can die away

in the fullness of balance--

molecules united

by the lack of moving.

grinding gasping tongue,

crushing blood. An itch

subdued but soreness

aches between lips. Charred

metal ringing like a church

bell against gums. I feel

good. Self-destruction

trickles down my spine

and makes me cold

at night. But I dream

about warming my body,

holding fur to stinging steel

and waiting for the heat

to diffuse. I lather myself

in the juxtaposition of fresh

and burn. I will wait until

my body reaches equilibrium,

until I can die away

in the fullness of balance--

molecules united

by the lack of moving.

Divya Mehrish is a high school senior from NY. Her writing has been commended by the Foyle Young Poets of the Year Award and the Scholastic Writing Awards, which named her a recipient of National Gold and Silver Medals. Her work has been published in the Ricochet Review, the Tulane Review, Body Without Organs, and Amtrak's Onboard Magazine The National. Most recently, the Arizona State Poetry Society's 2019 Annual Contest named her the winner of the Young Poets Award.

Thomas Price - The Krewe of Ghosts Rides Down Elysian Fields

Every Sunday night, just as the sun is about to extinguish at the horizon, people gather in the neutral ground and along the curb of Elysian Fields Boulevard, anticipating the ethereal ride of the ghost bikes. No one knows how or when the ghosts first appeared, and no one seems to care. The crowd is full of mamas and their babies and middle-aged white men in watermelon print Hawaiian shirts. Families with grills and men with greasy paper bags of fried chicken and even drunk tourists wandering in with off-season Mardi Gras beads plucked from the dirt under streetcar lines.

There is music there, traditional and contemporary. Groups of children, their trumpets and trombones pointing toward the sky, cheeks puffed. All blending with the hoots and laughs and call-and-response from the crowd. Suddenly a woman in bright purple is dancing in the middle of Elysian Fields. Her long braids bounce off her shoulders as she is moved by one of the many songs or, perhaps, a song only she can hear. There is a brief moment where all attention turns to her ecstatic performance. She is not alone for long as more women move out to her. And then men, too. A whole crowd of dancers filled with joy. Little boys and girls mimic their elders. Soon the street is full like a dance party.

As the sun disappears under the horizon, the energy in the crowd grows like static electricity: the charge of all the lives rubbing together. Sweat soaked in the miserable humidity, the bodies glisten. And they all sing and dance and cry out in a fever pitch until the sun is gone. Then, right before the streetlights click on, the crowd goes silent. They move out of the street, and all attention turns to a towering sculpture in the neutral ground: a twisting spire of bicycles welded together, painted white, an altar to lost souls. The only sound is the burbling of an infant blowing spit bubbles.

The excitement of the crowd starts to rumble again as spectral mist seeps from the sculpture, swirling and coalescing, then dropping to the street like sopping cotton. The concentrated mist pulses, growing bulbous tumors that suddenly collapse, little tentacles that flip around erratically before disappearing. And then it takes form: Wheels. Pedals. Frames of cruisers and tandems and BMXs. Then limbs, feet, and torsos. The ghosts of young and old. Just as the dusk turns to night, the ghost riders illuminate the faces of the spectators like the glow of flambeaux, their ex-bioluminescence the color of wintergreen. The bicycle bells begin to ring in chorus, echoing like a call through water. Voices of the dead.

The crowd responses with “Ride on! Ride on!” But just then, a black woman runs out into the street. She clutches a bundle, what looks like a baby, and she falls to the asphalt after the strap of her sandal breaks.

“They took my world,” she cries.

Several women run into the street to help her up, but she wrestles away from them. As she does, many in the crowd see that the bundle she clutches isn’t an infant. It is a teddy bear.

“They took my world,” she screams again. Her voice goes hoarse, and she just cries, with the teddy bear to her chest.

The crowd begins to yell at her, but the ghosts don’t pay any mind to them. Instead they stare down at the woman kneeling before them, and she looks back at them. She whispers, “They took my world.”

The ghosts silently agree, suddenly pedaling off, encircling the woman. The crowd watches something they have never seen before. They aren’t sure what the new trick is supposed to be because the crowd doesn’t know that there is one absolute thing the krewe of ghosts remembers: the tragedy of death.

The crowd backs away from Elysian Fields as the murmur of panic spreads. The mood of joy flips to fear, at the anger of the riders, who pick up speed until they are nothing but an ectoplasmic funnel of vicious mist. The woman’s hair whips in the force of the air. With her face bathed in green light, her eyes grow wide as she sees something in the vortex of the mist, the only thing she wants, and reaches out her hand, although she can never touch it. But the thought of touch, even in the face of its impossibility, is enough for her, at that moment.

Then the mist rockets up the street, opposite the normal route. Police on horses try to hold the line in the crosswalk at St. Claude, protecting the stopped traffic. But the horses can’t be controlled and canter off moments before the force of ghosts reaches them. The mist blasts into the traffic jam, the concussive force of a tidal wave. The fronts of cars are crushed; rear ends smash into the vehicles behind. Others are tossed aside like children’s toys, colliding into oak trees and streetlights. They drop through roofs of houses. They shred in twisted metal and rupture into balls of fire.

The woman stands alone in the street, calm, hugging the teddy bear, and she whispers, “They took my world.”

Now, no crowds will gather on Elysian Fields on Sunday nights. No trombones or drums. No joy of dancing. Instead, in the glow of late afternoon, people arrive to light candles placed on the curb. They leave little metal dishes of holy water and piles of magnolia flowers and jasmine around the sculpture. They toss offerings of bread and chicken feathers and coins into the street. They whisper little prayers in different languages and perform rituals from different faiths. But no one stays after the sun sets, and the spectral riders parade, unobserved and silent, except for the ringing of their bells, because the living has learned that the krewe of ghosts remembers.

There is music there, traditional and contemporary. Groups of children, their trumpets and trombones pointing toward the sky, cheeks puffed. All blending with the hoots and laughs and call-and-response from the crowd. Suddenly a woman in bright purple is dancing in the middle of Elysian Fields. Her long braids bounce off her shoulders as she is moved by one of the many songs or, perhaps, a song only she can hear. There is a brief moment where all attention turns to her ecstatic performance. She is not alone for long as more women move out to her. And then men, too. A whole crowd of dancers filled with joy. Little boys and girls mimic their elders. Soon the street is full like a dance party.

As the sun disappears under the horizon, the energy in the crowd grows like static electricity: the charge of all the lives rubbing together. Sweat soaked in the miserable humidity, the bodies glisten. And they all sing and dance and cry out in a fever pitch until the sun is gone. Then, right before the streetlights click on, the crowd goes silent. They move out of the street, and all attention turns to a towering sculpture in the neutral ground: a twisting spire of bicycles welded together, painted white, an altar to lost souls. The only sound is the burbling of an infant blowing spit bubbles.

The excitement of the crowd starts to rumble again as spectral mist seeps from the sculpture, swirling and coalescing, then dropping to the street like sopping cotton. The concentrated mist pulses, growing bulbous tumors that suddenly collapse, little tentacles that flip around erratically before disappearing. And then it takes form: Wheels. Pedals. Frames of cruisers and tandems and BMXs. Then limbs, feet, and torsos. The ghosts of young and old. Just as the dusk turns to night, the ghost riders illuminate the faces of the spectators like the glow of flambeaux, their ex-bioluminescence the color of wintergreen. The bicycle bells begin to ring in chorus, echoing like a call through water. Voices of the dead.

The crowd responses with “Ride on! Ride on!” But just then, a black woman runs out into the street. She clutches a bundle, what looks like a baby, and she falls to the asphalt after the strap of her sandal breaks.

“They took my world,” she cries.

Several women run into the street to help her up, but she wrestles away from them. As she does, many in the crowd see that the bundle she clutches isn’t an infant. It is a teddy bear.

“They took my world,” she screams again. Her voice goes hoarse, and she just cries, with the teddy bear to her chest.

The crowd begins to yell at her, but the ghosts don’t pay any mind to them. Instead they stare down at the woman kneeling before them, and she looks back at them. She whispers, “They took my world.”

The ghosts silently agree, suddenly pedaling off, encircling the woman. The crowd watches something they have never seen before. They aren’t sure what the new trick is supposed to be because the crowd doesn’t know that there is one absolute thing the krewe of ghosts remembers: the tragedy of death.

The crowd backs away from Elysian Fields as the murmur of panic spreads. The mood of joy flips to fear, at the anger of the riders, who pick up speed until they are nothing but an ectoplasmic funnel of vicious mist. The woman’s hair whips in the force of the air. With her face bathed in green light, her eyes grow wide as she sees something in the vortex of the mist, the only thing she wants, and reaches out her hand, although she can never touch it. But the thought of touch, even in the face of its impossibility, is enough for her, at that moment.

Then the mist rockets up the street, opposite the normal route. Police on horses try to hold the line in the crosswalk at St. Claude, protecting the stopped traffic. But the horses can’t be controlled and canter off moments before the force of ghosts reaches them. The mist blasts into the traffic jam, the concussive force of a tidal wave. The fronts of cars are crushed; rear ends smash into the vehicles behind. Others are tossed aside like children’s toys, colliding into oak trees and streetlights. They drop through roofs of houses. They shred in twisted metal and rupture into balls of fire.

The woman stands alone in the street, calm, hugging the teddy bear, and she whispers, “They took my world.”

Now, no crowds will gather on Elysian Fields on Sunday nights. No trombones or drums. No joy of dancing. Instead, in the glow of late afternoon, people arrive to light candles placed on the curb. They leave little metal dishes of holy water and piles of magnolia flowers and jasmine around the sculpture. They toss offerings of bread and chicken feathers and coins into the street. They whisper little prayers in different languages and perform rituals from different faiths. But no one stays after the sun sets, and the spectral riders parade, unobserved and silent, except for the ringing of their bells, because the living has learned that the krewe of ghosts remembers.

Thomas Price has an MFA from the University of New Orleans and is a Pasadena City College alumnus.

Crystal Salas - [We're Most Like Ghosts]

for Serafin Ramos Salas

We’re most like ghosts

in botanical gardens

in the city side

we don’t live

empty, weekday mornings--

admiring the work of the rose breeder:

crossed at the pollen

cut at the hip.

Bushes named after someone’s old auntie:

Minnie Pearl, Blanche, Heather,

never Maria, Consuelo, Lupe.

Benches bronzed with the names

of trustees, provosts,

philanthropists--

the rich dead,

considered by thousands

of daily visitors.

Who sees the camellias

we planted back at the house

next to the alleyway

the one that took you

sees your life?

We’re most like ghosts

in botanical gardens

in the city side

we don’t live

empty, weekday mornings--

admiring the work of the rose breeder:

crossed at the pollen

cut at the hip.

Bushes named after someone’s old auntie:

Minnie Pearl, Blanche, Heather,

never Maria, Consuelo, Lupe.

Benches bronzed with the names

of trustees, provosts,

philanthropists--

the rich dead,

considered by thousands

of daily visitors.

Who sees the camellias

we planted back at the house

next to the alleyway

the one that took you

sees your life?

Crystal AC Salas is a Chicanx poet, essayist, educator, and community organizer. She is currently pursuing her MFA at UC Riverside. She lives in Los Angeles where she writes about the city’s landscapes of grief and remembrance, it’s memorialized and un-memorialized spaces. She writes this poem in memory of her querido abuelito, Serafin, and in resistance against the gentrification of life and death.

Marie C. Lecrivain - La Santissima Muerte

On the night of Dia De Los Muertos

Santa Muerte appears on Olvera Street.

The crowds part in Her presence,

solicitous and reverent, and

a court of white-faced devotees

follow in Her wake, hands

extended for benediction

of bone against flesh.

Her delicate feet brush

against trails of marigolds

strewn in loving tribute

to that long ago time

when She could walk

among the living

without the presence

of the Cross and the Fire.

As Santa Muerte walks Olvera Street,

husbands cling to wives,

with nine levels of devotion,

and these women smile

as their wombs warm

to the promise of new life

kindled by fear of annihilation.

Her bald grin shocks crying babies

into silence as they stare

– wide-eyed and unbelieving -

in karmic recognition of First Mother

who sang paper-dry lullabies

and cradled each of them

in Her dusty arms

as She guided their souls

from old engines into new;

and a host of silver strings

within tiny hearts thrum with longing.

Santa Muerte lingers among ofrendas

that decorate the plaza,

her white cerements glowing blue

from the neon splendor

of downtown lights

that deepen the depth

of Her sightless orbs

as She dances with the calacas

in time to snapping fingers

and pan pipes that weave

rhythms and ribbons of time

to bind the past to the present

to the future to this moment,

and with one last silent laugh,

She disappears into the night.

Santa Muerte appears on Olvera Street.

The crowds part in Her presence,

solicitous and reverent, and

a court of white-faced devotees

follow in Her wake, hands

extended for benediction

of bone against flesh.

Her delicate feet brush

against trails of marigolds

strewn in loving tribute

to that long ago time

when She could walk

among the living

without the presence

of the Cross and the Fire.

As Santa Muerte walks Olvera Street,

husbands cling to wives,

with nine levels of devotion,

and these women smile

as their wombs warm

to the promise of new life

kindled by fear of annihilation.

Her bald grin shocks crying babies

into silence as they stare

– wide-eyed and unbelieving -

in karmic recognition of First Mother

who sang paper-dry lullabies

and cradled each of them

in Her dusty arms

as She guided their souls

from old engines into new;

and a host of silver strings

within tiny hearts thrum with longing.

Santa Muerte lingers among ofrendas

that decorate the plaza,

her white cerements glowing blue

from the neon splendor

of downtown lights

that deepen the depth

of Her sightless orbs

as She dances with the calacas

in time to snapping fingers

and pan pipes that weave

rhythms and ribbons of time

to bind the past to the present

to the future to this moment,

and with one last silent laugh,

She disappears into the night.

Marie C Lecrivain is the executive editor/publisher of poeticdiversity: the litzine of Los Angeles, a photographer, and is a writer-in-residence at her apartment. Her work has appeared in a number of journals and anthologies, including: Edgar Allen Poetry Journal, The Los Angeles Review, Lummox, Nonbinary Review, Spillway, Orbis, A New Ulster, and others. She's the author of several volumes of poetry and fiction, including the upcoming Fourth Planet From the Sun (© 2020 Rum Razor Press).

Matt McGee - Every Day is Dia De Los Muertos When You're Irish

Francisco the barback walks up to me

he's wearing white face paint in loose

2019 Joker fashion and says:

'You gonna celebrate los Muertos manana?'

Not one to question a psychopath, I say

'Can't. All my dead are buried back in Pennsylvania.'

When he shrugs I can see the ring of white face paint

around his collar, the kind his wife

is going to scrub by hand if she doesn't want

to kick in another $8 for another work shirt

'So? You go to Pennsylvania!’ he says. ‘How far can it be?'

Far, I say. 'Not as far as mi mama traveled.'

I ask where is she and he says 'She's dead. But

she walked here from Mazatlan. The least I can do

is walk to her grave in Beverly Hills.'

Across the bar sits Jerry. Earlier this year

he showed me the Momondo app, where cheap airfares

are compiled. Before I have time to think about

why Francisco's mother insisted on being buried in Beverly Hills,

I tap on the app and find a roundtrip flight

to Philadelphia for only $288 and think how,

sitting in our kitchens we always talk about people who’re gone,

‘remember when so-and-so did this?!’ because when you’re Irish

every day is Dia de los Muertos, and after all the trials Dad

endured to bring a family of six all the way to LA in the 70's

the least I can do is spend five hours backtracking

to pay a few respects in a rainy, hilltop graveyard

on a November day most life-long Pennsylvanians

don't think of as different from any other.

he's wearing white face paint in loose

2019 Joker fashion and says:

'You gonna celebrate los Muertos manana?'

Not one to question a psychopath, I say

'Can't. All my dead are buried back in Pennsylvania.'

When he shrugs I can see the ring of white face paint

around his collar, the kind his wife

is going to scrub by hand if she doesn't want

to kick in another $8 for another work shirt

'So? You go to Pennsylvania!’ he says. ‘How far can it be?'

Far, I say. 'Not as far as mi mama traveled.'

I ask where is she and he says 'She's dead. But

she walked here from Mazatlan. The least I can do

is walk to her grave in Beverly Hills.'

Across the bar sits Jerry. Earlier this year

he showed me the Momondo app, where cheap airfares

are compiled. Before I have time to think about

why Francisco's mother insisted on being buried in Beverly Hills,

I tap on the app and find a roundtrip flight

to Philadelphia for only $288 and think how,

sitting in our kitchens we always talk about people who’re gone,

‘remember when so-and-so did this?!’ because when you’re Irish

every day is Dia de los Muertos, and after all the trials Dad

endured to bring a family of six all the way to LA in the 70's

the least I can do is spend five hours backtracking

to pay a few respects in a rainy, hilltop graveyard

on a November day most life-long Pennsylvanians

don't think of as different from any other.

MATT McGEE writes short fiction in the Los Angeles area. When not typing he drives around in a vintage Mazda and plays goalie in local hockey leagues.

Cailey Thiessen - Ofrendas for a Country

I wanted to title this,

ofrendas for my country.

But the my sticks in my throat

like too thick atole.

I’m building an altar to Mexico.

Carefully painted flowers,

pan de muerto made by hand

(kneaded with anger and loss),

thick chocolate with cinnamon

to fill the empty spaces.

In childhood I walked past them,

head down, eyes tilted

to stare at the flowers—the food.

“Why do we cook for them?

The dead are no longer here.”

But now the dead sing from the halls.

The absence of guitars

is chilling. I light candles

to ward off the silence.

All night the altar sits untouched.

I am too far away for the spirits

to wander so long from home.

ofrendas for my country.

But the my sticks in my throat

like too thick atole.

I’m building an altar to Mexico.

Carefully painted flowers,

pan de muerto made by hand

(kneaded with anger and loss),

thick chocolate with cinnamon

to fill the empty spaces.

In childhood I walked past them,

head down, eyes tilted

to stare at the flowers—the food.

“Why do we cook for them?

The dead are no longer here.”

But now the dead sing from the halls.

The absence of guitars

is chilling. I light candles

to ward off the silence.

All night the altar sits untouched.

I am too far away for the spirits

to wander so long from home.

Cailey Johanna grew up across Mexico and the United States. She writes in English and Spanish and sometimes a mix of the two. She graduated from Champlain College with a degree in Professional Writing and now lives in Georgia and works as a freelance writer. Poetry will always have her heart, as will Mexico, cacti, and that weird little fish called an axolotl. Her poems have been published in Willard & Maple, Hispanecdotes, Cecile's Writers, and more.

Trudy Hale - Love Letter from an Ex-Wife

Your social worker left a message--

you kicked a nurse in the stomach.

It was night when they came into your room,

like witches, you tell me, to change your diaper.

You called me, terrified that they will kick

you out, out of your room

with a balcony and view of the mountains where you once

shot a Western, in the hills of wild grasses before the McMansions.

Today you can't shuffle to the bathroom or down the hall

to the elevator, to the dining room, to the white linen tables

to sit with the others, the ladies and gents. You can't stand

all those old people, you say, and it's hard to believe it happened so fast--

that you went from being you to an old man who sometimes drools,

slips out of his wheelchair. This is how they must see you, the nurses

who come in the night and roll you to the left, then to the right.

But you are not who they think, but quite a different fellow,

a dashing someone in a fast sports car speeding into gold hills,

along glittery roads, paths everlasting, faster and faster;

a white silk scarf, a purple beret aslant,

cocked over one eye, like a pirate's patch,

a willow-wind joy, a urine-soaked sheet, and a kick

to banish those rough hands in the dark night.

you kicked a nurse in the stomach.

It was night when they came into your room,

like witches, you tell me, to change your diaper.

You called me, terrified that they will kick

you out, out of your room

with a balcony and view of the mountains where you once

shot a Western, in the hills of wild grasses before the McMansions.

Today you can't shuffle to the bathroom or down the hall

to the elevator, to the dining room, to the white linen tables

to sit with the others, the ladies and gents. You can't stand

all those old people, you say, and it's hard to believe it happened so fast--

that you went from being you to an old man who sometimes drools,

slips out of his wheelchair. This is how they must see you, the nurses

who come in the night and roll you to the left, then to the right.

But you are not who they think, but quite a different fellow,

a dashing someone in a fast sports car speeding into gold hills,

along glittery roads, paths everlasting, faster and faster;

a white silk scarf, a purple beret aslant,

cocked over one eye, like a pirate's patch,

a willow-wind joy, a urine-soaked sheet, and a kick

to banish those rough hands in the dark night.

Trudy Hale, diarist, poet, and teacher, wears many literary hats. She runs Porches Writing Retreat in Nelson County, Virginia. Born in Memphis she lived a somewhat chaotic and semi-glamorous life in Hollywood, married to a director and raising their two children. She moved to Virginia (long story still in rewrites), and opened Porches, a retreat that supports and encourages writers of all stripes, regardless of age or checkered past. You can find out more about her on www.porcheswritingretreat.com

Samantha Simpson - The Last Judgment of Wanda

…and then the world ended.

The apocalypse melted the depot—the same depot that had survived Sherman’s razing in 1864 and Bernadette Tilden’s craft seminar in 1982. The high school sank into the roiling muck, and what was left of the bowling alley burst into cement and plaster confetti. The AME church where Lester Poole shot all those boys and girls folded itself in half and in half and in half until nothing remained except a sliver of a steeple. The grocery store exploded, and the believers danced and shouted in the torrent of ground chuck. The church mothers from Bethlehem Baptist—the one out on Route 15—clutched their plumed hats and watched the sky boil orange and purple. Their hearts most likely pounded a gospel rhythm inside their rib cages, and they sang until their throats were raw.

That was a Friday afternoon in April—the last Friday ever, the final April in human history. In the minute before the world ended, Wanda Brown stood paces away from the library entrance. Her armpit warmed a paperback copy of Doctor Faustus, and she angrily slurped cherry ICEE out of a paper cup. She glared through the glass double doors at the new librarian, who did not wear cat’s-eye glasses or paisley tunic tops. This new librarian didn’t know where to find The Epic of Gilgamesh or how to replace the ribbon in the typewriter that still squatted next to the row of humming PCs. What’s more, this new librarian said Wanda couldn’t bring any drinks into the stacks—no, not even with a lid—and Wanda hated her.

Seconds before a tide of blood crushed the library, Wanda crushed the paper cup and tossed it in the garbage can. Her trig homework and AP US history essay cast a dark cloud over the afternoon, and the last thing--the actual last thing--she wished for was an hour to read. She saw a quarter gleaming at her from the sidewalk. Wanda bent to pick it up right before it--that is, the entire world--was over. In that final moment, her pants slipped past her hips and exposed the top of her butt crack to what was left of her town.

Now she had a literal eternity to live it down--not that anyone could see her through the relentless waves of mud and viscera coursing through the remains of Jonesville. Wanda had to front crawl through a lake of congealing blood before she reached dry land--or the hunk of concrete that used to be her elementary school. The sky grumbled above her head, and bolts of white lightning cut through the dark clouds.

The apocalypse melted the depot—the same depot that had survived Sherman’s razing in 1864 and Bernadette Tilden’s craft seminar in 1982. The high school sank into the roiling muck, and what was left of the bowling alley burst into cement and plaster confetti. The AME church where Lester Poole shot all those boys and girls folded itself in half and in half and in half until nothing remained except a sliver of a steeple. The grocery store exploded, and the believers danced and shouted in the torrent of ground chuck. The church mothers from Bethlehem Baptist—the one out on Route 15—clutched their plumed hats and watched the sky boil orange and purple. Their hearts most likely pounded a gospel rhythm inside their rib cages, and they sang until their throats were raw.

That was a Friday afternoon in April—the last Friday ever, the final April in human history. In the minute before the world ended, Wanda Brown stood paces away from the library entrance. Her armpit warmed a paperback copy of Doctor Faustus, and she angrily slurped cherry ICEE out of a paper cup. She glared through the glass double doors at the new librarian, who did not wear cat’s-eye glasses or paisley tunic tops. This new librarian didn’t know where to find The Epic of Gilgamesh or how to replace the ribbon in the typewriter that still squatted next to the row of humming PCs. What’s more, this new librarian said Wanda couldn’t bring any drinks into the stacks—no, not even with a lid—and Wanda hated her.

Seconds before a tide of blood crushed the library, Wanda crushed the paper cup and tossed it in the garbage can. Her trig homework and AP US history essay cast a dark cloud over the afternoon, and the last thing--the actual last thing--she wished for was an hour to read. She saw a quarter gleaming at her from the sidewalk. Wanda bent to pick it up right before it--that is, the entire world--was over. In that final moment, her pants slipped past her hips and exposed the top of her butt crack to what was left of her town.

Now she had a literal eternity to live it down--not that anyone could see her through the relentless waves of mud and viscera coursing through the remains of Jonesville. Wanda had to front crawl through a lake of congealing blood before she reached dry land--or the hunk of concrete that used to be her elementary school. The sky grumbled above her head, and bolts of white lightning cut through the dark clouds.

In real life, Samantha teaches at an all-girls school in Boston. She's an instructor for the Young Writers at Kenyon program each summer at Kenyon College. Her fiction and non-fiction have appeared in The Kenyon Review, REAL, Prism Review, and Crazy Horse. She is currently at work on a novel about time travel.

Jenny Patton - Candyman

I’ve forgotten your name, how your wife died

and which house it was over on Ardmore Road,

the one with the balcony or the wayward Chinese elm.

Thirty years later, they are different,

none white. I remember your nods and grunts,

your lanky frame, your rust-colored plaid shirts

and squished-up expression when you handed us

candy from your open palms. We neighbor kids

came so you’d feel less alone, our visits a duty,

our job to take. Do you know Widow Hoy? I asked,

thinking the candy people must know each other.

You shook your head then mumbled; I saw myself

in the flat reflection of your winged glasses.

She’s the candy lady on Doresta. She appeared

when we pushed her lighted bell,

carrying a glass bowl with hard caramels

wrapped in gold cellophane, the lady

who drove the Chevy arc around town.

When I told Mom you should marry Hoy,

I was forbidden from your street, from you.

Now I wonder why she feared you.

Were you dangerous? I kept coming, alone,

pretending it was Halloween in June,

my costume a striped bathing suit and two-

tone Dolphin shorts. I banged your door and stayed

in your driveway when you didn’t answer,

picking lavender honeysuckle bells

from your hedge. The older kids taught me to

detach them gently, touch them with my lips

and suck the thick sweetness from the white base.

I kept the substance in my mouth longer

than I should, swallowing, then wanting more.

and which house it was over on Ardmore Road,

the one with the balcony or the wayward Chinese elm.

Thirty years later, they are different,

none white. I remember your nods and grunts,

your lanky frame, your rust-colored plaid shirts

and squished-up expression when you handed us

candy from your open palms. We neighbor kids

came so you’d feel less alone, our visits a duty,

our job to take. Do you know Widow Hoy? I asked,

thinking the candy people must know each other.

You shook your head then mumbled; I saw myself

in the flat reflection of your winged glasses.

She’s the candy lady on Doresta. She appeared

when we pushed her lighted bell,

carrying a glass bowl with hard caramels

wrapped in gold cellophane, the lady

who drove the Chevy arc around town.

When I told Mom you should marry Hoy,

I was forbidden from your street, from you.

Now I wonder why she feared you.

Were you dangerous? I kept coming, alone,

pretending it was Halloween in June,

my costume a striped bathing suit and two-

tone Dolphin shorts. I banged your door and stayed

in your driveway when you didn’t answer,

picking lavender honeysuckle bells

from your hedge. The older kids taught me to

detach them gently, touch them with my lips

and suck the thick sweetness from the white base.

I kept the substance in my mouth longer

than I should, swallowing, then wanting more.

Jenny Patton, a Pasadena native, teaches writing at Ohio State University. Her stories and essays have been published in Brevity, River Teeth online, Kaleidoscope, Natural Awakenings, Prism Review and 751 Magazine among other places. An avid journaler, she posts writing prompts at journalingwithjenny.blogspot.com.

Leanor Johansen - Love lives on

Leanor says: "Poetry is the song of my soul attempting to release endless intrepid thoughts of my beautiful intricate mind. It's the outlet of my life experiences in the breath of my core feelings at the deepest level of my DNA. Psychologist by day, professor by night, poet at heart, a soul existing to write."

CONTRIBUTE TO THE INSCAPE ALTAR FOR THE DEAD

Contribute your own ofrendas below by clicking the plus sign!

Inscape Staff reserve the right to delete or omit posts that are offensive or otherwise not appropriate for our community.

Proudly powered by Weebly