- Folio No. 9

- About

- Feral Parrot : The Blog

- INTERVIEWS

- SUBMISSIONS

-

ISSUE ARCHIVE

- PRINT Chapbook No.6 Healing Arts

- Online Issue No.9

- Online Issue No.1 Fall 2016

- Online Issue No.2 Spring 2017

- ONLINE Issue No.3 Fall 2017

- PRINT Vol 72 No 2 Fall 2017

- PRINT Vol 73 No.1 Fall 2018

- ONLINE Issue No. 4 Fall 2018

- Online Issue No.5 Summer 2018

- FOLIO No.1 Fall 2018 VOTE

- ONLINE Issue No.6 Fall 2018 Fall Spirituality

- FOLIO 2 Fall 2019 Celebrating Dia De Los Muertos

- FOLIO No.3 -- Moon Moon Spring 2019

- FOLIO No.4 Celebrating New PCC Writers

- FOLIO No.5 City of Redemption

- FOLIO No.6 Spring 2020

- FOLIO No. 7 - Winter 2021 Into the Forest

- 2022 Handley Awards

- Inscape Alumni Board

- PRINT Chapbook No. 7 Healing Arts

- Blog

- Untitled

Interview by Frank Turrisi

|

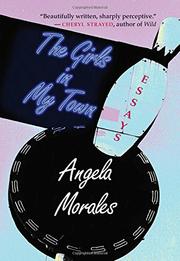

This year's winner of the prestigious PEN/Diamonstein-Spielvogel Award for the Art of The Essay hails from our hometown of Pasadena and teaches Creative Writing at Glendale Community College

Inscape Magazine Blog Editor, Frank Turrisi, recently caught up with Angela in-person to talk about her book THE GIRLS IN MY TOWN, creative writing, the open college system, DACA, and how life can both inspire AND get in a writer's way. You can catch Angela Morales reading at Pasadena City College on Tuesday, November 28 in Harbeson Hall from 12:15 p.m.-1 p.m., as part of the Creative Writing program's Visiting Writers Series sponsored by a grant from the Pasadena Festival of Women Authors. |

FT: You hold an MFA from one of the much-celebrated meccas of creative writing, the University of Iowa, and its Iowa Writers’ Workshop. Can you explain the process of your admission for the Creative Writing students that wish to follow in your footsteps?

AM: The piece that I sent with my application was a short, personal essay about my grandmother. I would say it was about 12 pages long, and my grades at UC Davis were pretty mediocre. So. It had nothing to do with grades. It was all solely based on those 12 pages, and that was the only place that I wanted to go. So, I didn't apply to any other creative writing programs.

FT: What was the process within the workshop like, and how did it help shape you as a writer today?

AM: When you're in the creative writing program, the way I look at it is, it gives you dedicated time to write. You can be a great writer without it. You have to fight harder for it that way, and the workshop process will really help to a point. So, I'd say for the first two years I was there, I really listened hard to what people told me. I really tried to hear them out, learn, and realized that after two years I didn't want to hear it anymore. So, when people would start workshopping I would get frustrated. I kind of started to say, I'm out of here. I'm going to go do this. So, I think for every writer you have a saturation point, where you go to learn there and you learn. Then, it’s like, I'm done. I just need to go do. That's what happened to me. So, by the time I got out of there, I was just ready to be done. But, I didn't start publishing after for another 15 years. So I took it and went underground with that knowledge. Then I went to teach.

FT: You’re also a professor of English and Creative Writing. In your essay Bloodyfeathers, which you describe having a murderous ex-con as a student, you quote lines from Emma Lazarus’s sonnet “The New Colossus”, the very words inscribed inside of the Statue of Liberty monument; “Give me your tired, your poor,/Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,/The wretched refuse of your teeming shore,” and you make a powerful connection between these lines and your similar beliefs of an open college system. Will you elaborate on this?

AM: I believe that the college system should not be elitist, and that it should be accessible for anybody, of any age, or any economic background, or culture. And, that it should be open to anyone who wants to learn. However, you get all types. All kinds of characters. Types of people who challenge your definition of what a student is. So, that's been interesting for me. You learn about the problems that these students have. But, part of the privacy protections that are built into, the kind of rules of the school are, that you don't have a right to know a person's past, their criminal history, or their medical history or anything because you want it to be equal. You want everyone to be able to have a fair shot. So, Bloodyfeathers, you know, who was an ex-con, killed a guy. If, I would’ve known that before he walked in the classroom, I might have judged him a little differently. So who knows? There are moments when you come head to head with the problems associated with those privacies. So it was quite a shock.

FT: You must have a lot more psychological insight, to the student, just by the nature of teaching the subject Creative Writing. Is there an example of someone/something where this system (college) really failed, affecting your job (negatively)?

AM: I had a student who committed suicide. I could see signs of his distress in the classroom. But, also, he turned in an essay in which he talked about wrestling with demons, and being chased by demons. And so, when I reported it to counselors they said that there was nothing that they could do, other than, I could tell him go talk to somebody on campus. Like, a mental health counselor. And, they do what they can, but it's so basic. And so, you know, so much more just based on stress. They’ll suggest he go see someone else. So, knowing that this poor guy was struggling with these demons, and then after that, hearing that he committed suicide, it was just brutal. It was a bad week for me, because it made me feel pretty helpless as an instructor. But then also, like, to know that in writing, there are clues. Cries for help or whatever. But then there’s nothing you can really do, other than be kind, and kind of push them in the right direction if they need to talk to somebody else. So, that’s been challenging.

FT: Yes, and then there’s the need to do your writing on top of that. So, to quote Nora Ephron, “The hardest part of writing is writing.” Anybody that writes can echo this in various ways. As a professor/mother of 2 living in Los Angeles, what kind of routine must you keep to write at the level that you do, and how are you able to maintain it? Do you have any great motivators/secrets that you can share on how you keep producing such high caliber work?

AM: Wow. Thanks! That’s up for dispute, but okay. I do (have some secrets). I literally go to a desert island. By myself. I'm not kidding! I will take myself to Santa Rosa Island in the Channel Islands with my backpack, my tent, and a notebook. I do! I will go out there for like three days. And there's no services. It's just a campground and a beautiful beach and trails. So I'll take my little chair and my notebook, and I’ll just go start writing. And, I feel like I'm kind of the weirdo out there, because everybody else is there in small groups. Like campers (and such). I'm like this person, like this woman, sitting all by herself. I have to! I have to get away from like Wi-fi, and…

FT: But that’s not a daily routine. How do you manage to write on a regular basis?

AM: I don't think I do it on a regular basis. I, like, binge write. I'm trying to get better at being more regular. Like, you know, just writing for 10 minutes here and there. But I'm a total binge writer. I could write for like 15 hours straight without stopping. But, yeah it's hard on the daily. I don't (write on the daily, but…). I try. I try. Yeah. Yeah!

FT: You are a woman of Mexican heritage. The University of New Mexico Press, the publishers of your book, are one of the most respected in the field of Chicana/o Studies. They took your collection of previously published essays to form your book “The Girls In My Town,” such a wonderful and eclectic group of stories that resonate with many important themes, yet through a cohesive voice. If there is one message that you would like the Chicana/o people to take from the book, what would it be?

AM: I would like it to be that there is no one experience for Latinos or Mexican-Americans. And, that there has been a lot of great writing from Mexican-American/Chicano writers, but we're all different. We all come from different socioeconomic groups in different parts of the United States. So I grew up, you know, like in the 70s and 80s in Los Angeles and I grew up as a middle class, fairly comfortable person who never had to struggle with being poor. I had other struggles, but some people have told me what I write is not “Mexican enough”. Like this (book) now doesn't count as Chicano literature (she asserts), because I don't call it that. So, I find that to be kind of sad. I don’t think that there should be any correct definition of what that should be (Chicano Literature).

FT: We are in Trump’s America, with talks of walls, deportation, xenophobic sentiments filling our airwaves, and the phasing out of DACA. What insight has teaching creative writing in the Los Angeles area given you into the perspective of the “dreamers”? Is there any particular work/merits of one of your students that stands out in your mind, and that states the strongest case for keeping DACA?

AM: I had a student, his name was Sergio, and he is a model student. He does everything right. He's on student government. He gets good grades. He played on the football team. And, he wrote this beautiful essay about that. About being brought here as a child and wanting to contribute to society, and now being against a stone wall where the country that you love, and the country that you embrace, doesn’t want a place for you. And he wrote about it so beautifully. I just felt like he could kind of be the poster-child for DACA. But, it really came through in his writing. I think he really educated the class too. About what that means, because in our class we have a lot of immigrants who came in “the right way”.

And so, I think they sometimes don't understand illegal immigrants and their plight, and like, why a person would flee from El Salvador, or why a person would come from a really poor place in Mexico and risk their lives. So they just think, Yeah, those people broke the law, and they need to wait in line just like we did. They don't understand the urgency of why people come, but I think Sergio's story really helped a lot of people to understand that DACA is not just a bunch of faceless people, but that they are real people sitting right next to you. Who we should not just have compassion for, but that we should fight for.

FT: To reference the title essay of your book, you were not one of “The Girls In Your Town.” That is, to say, a statistic of teenage pregnancy, and the largest demographic of which (in California) are Latina. I have a statistic. An article in The Fresno Bee from August 2016 states that since the year 2000, the adolescent birthrate among California Hispanics declined from 77.3 to 31.3, with “your town” of Merced slightly higher at 36.2. After discussing in your book with alarming concern (to me), the cyclical nature of the incidence of teen pregnancy and witnessing how so many of these families repeat this behavior generationally, what do you make of this statistic?

AM: Yeah! I think it’s great! But, I would say it (Merced) was kind of a culture within a culture, because in that small town it’s so common. I think a lot of girls look at other girls and they see you can have a baby when you’re seventeen. You can have a stroller and all these cute little things. And, you can have this cute little kid you can parade around the park. You have a living doll, someone to love you. I think when you grow up in a rough place like that, kind of poor, your parents, everybody’s kind of depressed. The Central Valley is kind of ugly, because it’s been so depleted by agriculture and all. I think I try to say this at the end of the essay. That, “A baby is like a thing of beauty, that you can look at as a symbol of the future”. So, it’s not all bad, but unfortunately a lot of the cycle repeats itself. You’re not the best parent when you’re 16 or 17 because you’re a baby yourself.

FT: Is it the way that society has shifted, dealing with this issue, or the way that Latino culture is moving forward (since you wrote the essay), that contributes to the decline (in that statistic)?

AM: I would love to go back and study that. Try to figure out what is accounting for that. But, maybe we're (society) doing a better job in giving teenage girls the message that there are scholarships available, a lot of alternatives. I think for a lot of kids it was like you’re either going to college or you’re not going to college. Like, you’re a smart one, or you’re a dumb one. I think a lot of teachers and counselors are getting better at showing the kids there are many alternatives. You know, like, you can go to the community college. You can take online classes. You can (also) get, not a degree, but a certificate. So, hopefully that's part of the change. (Morales ponders) Better access to healthcare. That could be. Now, if Trump has his way, God knows what will happen. Right? One thing that I was thinking of that has changed since I was there is the University of California. UC Merced is now fully established. I wonder if that makes a difference. Interesting…

FT: From reading your book, I learned the following things about you. Tell me what the following things taught you about yourself: Bowling a 274

I’m awesome! No, that was one of those things where nobody was there to witness it. So, I still believe if nobody was there to see it, and nobody was there to cheer you on, it almost, really didn’t happen. I guess the lesson is, sometimes you can do a really great thing without recognition, and you should just be satisfied with that. You should just be proud of yourself even if nobody knows about it.

FT: Encountering a mountain lion on your bicycle

AM: Ummm…that I have great…reflexes! I was so terrified when I saw those yellow eyes staring at me, that I basically disappeared. I fled the scene, but I think what I also like about that is I’m willing to put myself in dangerous places. And, I’m always proud to tell those stories because I realize you’re going to have to take risks if you’re ever really going to enjoy the world (she laughs). I saw a bobcat! Same spot. Same spot I saw this mountain lion, I saw a beautiful bobcat the other day. Standing in the middle of the road with her two babies. So, she just stopped and looked at me. Did I tell you about the grizzly bear?

FT: No, please do…

AM: I was in Alaska. I was doing this residency for Denali National Park, and they gave me a cabin to stay in for 10 days. It was 40 miles into the park, and it’s in the tundra, right. It’s a beautiful little cabin next to a river, and I had a satellite phone. They said use it if you have an emergency, you’ll contact the ranger station…which is 40 miles away, and we’ll try to get to you as soon as possible. And so, I said okay. And they said you shouldn’t have a problem. I had a car, and there was a dirt road. But, this one night, there were these windows that pull out, and you prop them open. They open this much (she gestures with her hands about 2-3 feet, plenty of room for the bear to break the window open).

One night, I left the windows propped open, and it only got dark for about 3 hours because it was summer. So, it’s like 2am-5am, it’s dark. The rest of the time it’s light. So, I’m sleeping and I hear scratching on the wall, and it’s like claws. I can hear it. It’s a grizzly bear, and it’s like, snorting! It had come out of the river, so it kept shaking off. It sounded like when a dog starts shaking off (its body) water, but imagine, like a 400 lb. dog. It was going around all sides of the cabin, and scratching, and scratching, and snorting. I had, like a can of bear spray, and the window was open, but you had to close the window from the outside. So, obviously I wasn’t going to close this window.

So, I thought, well, if he wants to get in, he’s going to get in. All he has to do is pull the window off and come in. That night, I had (eaten), like food. So, you know, I’d been making spaghetti and I have a bag of garbage by the door, and I'm like, I’m gonna die. And I really resigned myself. There’s no way I can fight this thing off, and if it wants to come in and kill me, it’s going to do it. So, I basically laid down and pulled the blankets over my head and said, I’m gonna die tonight.

It scratched like that for probably a good two hours, and then I didn’t hear anything for awhile. I thought, okay, thank God. By then, the sun was starting to come up, and the outhouse, of course, was outside. So I had to go outside. I pull the door open gently, nothing’s there, but there’s grizzly bear fur all over the wall. So, I realized what it was doing. It was scratching its back all over the cabin. It was like a scratching post, and then nails, I think, were like holding onto the wall. So, as I was taking tufts of golden grizzly bear hair, I thought, Wow, he didn’t even care about me. All this poor bear was doing was having a good ol’ time (she laughs).

It was such a weird feeling, because it was like, This is how people don’t survive in nature.

FT: What happened with the satellite phone?

AM: I never used it. I had too much pride. I didn’t wanna be like, Come help me (feigning a high-pitched, helpless voice). I looked at it, said, Should I? No, I gotta deal with this.

FT: Being uprooted without notice when your parents separated

AM: I think it taught me adults are really fucked up. Right?

FT: I can vouch for that.

AM: Because, I think that sometimes when you’re a kid, you want to think your parents have all the answers, and they’re always going to make the right decisions. But then, you realize that your parents are wrong (can be), and they might not be able to protect you, and you have to learn how to adapt to the mistakes that they make. I think a lot of kids are good at that. They just learn to adapt to their parents. You have no choice. If you’re going to survive as a kid, you have to learn to live with the rules your parents set, and the place they tell you that you have to live. Ultimately, some kids adapt better than other kids. I think that I was good at adapting though. So, I don’t have a lot of those hang-ups.

FT: Pointing a gun at your father

AM: Ah…what I learned about that is, I don’t have to put up with shit if I didn’t want to. You know, how you also think as a kid, I wish he would die. I wish he were dead. I don’t know, maybe you don’t have that experience (Morales giggles). But, I think a lot of us have that kind of flippant thought, I wish my Dad would die. But, I realized at that moment, I really didn’t want him to die. I just wanted him to go away. I just wanted him to disappear, and there’s a difference between killing someone and someone disappearing. So, I think having the gun in my hand made me understand that your life could go in different directions at any moment. It sounds kind of preachy, you know? But based on the choices we make, we go in that direction, or we go in this direction. I guess it became clear to me I didn’t want to go in that direction. Chances are, I probably would’ve fired the gun and missed, and nothing would’ve happened. Who knows? But, it was clear. I didn’t want to go in that direction.

FT: Living in a predominantly white neighborhood

AM: It taught me that I was Mexican. I’m not saying that to be silly, but I just thought for most of my childhood that I was like everybody else. That we’re all the same. I guess if I had been black, that wouldn’t have been possible (to think that way). But, because my family is fairly light-skinned Mexican-American we were kind of able to look like everybody else. But then, in that neighborhood, suddenly I’d have moments where the neighbor boys called me a beaner, and it kind of made me freeze a little bit. And I thought, Wow, nobody’s ever called me that before. It’s not like they were just saying, go away ugly. Go away you stupid girl, but they were actually calling me a name about my ethnicity. That was the first time that had ever happened. Then, I had a friend. She was my best friend, and I would go to her house. And one day, she told me her father didn’t like Mexicans. But it was okay for me to be there, because I was the good kind. So then, there were those moments that I realized that we weren’t all the same.

FT: You speak of a greater importance in the concept of heaven once you have children. In one of the essays in your book, you elegize every dog you’ve ever owned. Even though you inject a great deal of humor and folly in recounting these events, your writing is full of compassion and intelligent, moral decisions. That being said, there seems to be a connection to a serious hope for an afterlife in your work. If you get to meet your maker, what is the one thing you would ask forgiveness for?

AM: Wow! Who are you, Barbara Walters? What is this? (We share a laugh). I have so many things I would ask forgiveness for. But, I feel like I haven’t been a good family member all the time. Because, I tend to be very introverted. I like my privacy.

So, if there is a God, if I get to heaven, I would like to be forgiven for the times I removed myself from social situations. Or when during the party, went to go hide in my room. Or, not go (have gone) to see my aunt when she’s sick in the hospital. Or, the list goes on and on. I don’t think I’m like this on purpose. It’s just my personality. You try to write (and), you have to do a lot of thinking work. You have to be alone to do that. In solitude. So people don’t always understand that. They take it personally and think that you don’t like them. Or, that you’re just a bitch. So, I’d like to apologize for that.

FT: At this point, I think it is more than fair to say you’ve become a decorated writer. Your book has earned Editor’s Picks and several best book lists, you were the winner of the 2014 River Teeth Literary Nonfiction Award, the prestigious 2017 PEN/Diamonstein-Spielvogel Award for the Art of the Essay to name a few of your highest achievements. What do you feel is the most important thing you still have left to accomplish as a writer?

AM: Right now, I’m thinking I want to write short stories. I started writing fiction, and I pretty much suck at it. But, I love it. I love it! You know, like a guilty pleasure. I know that I’m not that good at it yet, but I feel that with each story that I write I’m getting better. So, my next goal is to write either a novel, or a collection of short stories and kind of cross the genre line. I still love non-fiction though. I love creative non-fiction, but I just have in my mind that I just want to write one beautiful short story. Then, I think I’ll be really happy with myself. And, what I will add, I don’t want it to be a story that feels like a true story. You know what I mean? Like it’s not just me in a fictional situation, but it is truly about another place, another time, completely different character.

FT: (Have left to accomplish) As a teacher?

AM: I want to say something practical. Like, to be better at teaching grammar. But, that’s so boring. (changes her mind) It's legitimate. I'll stick with the grammar. I think people are overlooking the importance of grammar these days. The seriousness of saying what you mean, and meaning what you say, and like, precisely wording sentences. And you know, because we text so much and we email so much, people are online all the time. And, I feel like language is getting really sloppy. So, I would hope that in the next few years, when I keep teaching, that I can really keep pounding the message in that words matter. Every word you say and write matters, and you should conserve those, and be as precise as possible.

FT: Do you want to add anything about your book “The Girls In My Town,” take a little opportunity for self-promotion?

AM: I wrote that book not knowing that it was going to be a book. So, I wrote each part of it individually, and each part led to another part of it. So, I’m proud of the fact that it feels about as natural as possible. I feel like it was written with pure intentions. Without the intention to sell it, or to write for any particular audience. I just felt like I wrote it because each of those stories was just super important to me, and I wanted to write them down before I forgot them. So, now that I’m working on a second book, I’m really struggling with, who is my audience? Why am I writing this? But with that first one, it was like…pure. And I’m very proud of that.

To learn more about Angela Morales and her work, visit her website, http://www.angelamorales.net/

AM: The piece that I sent with my application was a short, personal essay about my grandmother. I would say it was about 12 pages long, and my grades at UC Davis were pretty mediocre. So. It had nothing to do with grades. It was all solely based on those 12 pages, and that was the only place that I wanted to go. So, I didn't apply to any other creative writing programs.

FT: What was the process within the workshop like, and how did it help shape you as a writer today?

AM: When you're in the creative writing program, the way I look at it is, it gives you dedicated time to write. You can be a great writer without it. You have to fight harder for it that way, and the workshop process will really help to a point. So, I'd say for the first two years I was there, I really listened hard to what people told me. I really tried to hear them out, learn, and realized that after two years I didn't want to hear it anymore. So, when people would start workshopping I would get frustrated. I kind of started to say, I'm out of here. I'm going to go do this. So, I think for every writer you have a saturation point, where you go to learn there and you learn. Then, it’s like, I'm done. I just need to go do. That's what happened to me. So, by the time I got out of there, I was just ready to be done. But, I didn't start publishing after for another 15 years. So I took it and went underground with that knowledge. Then I went to teach.

FT: You’re also a professor of English and Creative Writing. In your essay Bloodyfeathers, which you describe having a murderous ex-con as a student, you quote lines from Emma Lazarus’s sonnet “The New Colossus”, the very words inscribed inside of the Statue of Liberty monument; “Give me your tired, your poor,/Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,/The wretched refuse of your teeming shore,” and you make a powerful connection between these lines and your similar beliefs of an open college system. Will you elaborate on this?

AM: I believe that the college system should not be elitist, and that it should be accessible for anybody, of any age, or any economic background, or culture. And, that it should be open to anyone who wants to learn. However, you get all types. All kinds of characters. Types of people who challenge your definition of what a student is. So, that's been interesting for me. You learn about the problems that these students have. But, part of the privacy protections that are built into, the kind of rules of the school are, that you don't have a right to know a person's past, their criminal history, or their medical history or anything because you want it to be equal. You want everyone to be able to have a fair shot. So, Bloodyfeathers, you know, who was an ex-con, killed a guy. If, I would’ve known that before he walked in the classroom, I might have judged him a little differently. So who knows? There are moments when you come head to head with the problems associated with those privacies. So it was quite a shock.

FT: You must have a lot more psychological insight, to the student, just by the nature of teaching the subject Creative Writing. Is there an example of someone/something where this system (college) really failed, affecting your job (negatively)?

AM: I had a student who committed suicide. I could see signs of his distress in the classroom. But, also, he turned in an essay in which he talked about wrestling with demons, and being chased by demons. And so, when I reported it to counselors they said that there was nothing that they could do, other than, I could tell him go talk to somebody on campus. Like, a mental health counselor. And, they do what they can, but it's so basic. And so, you know, so much more just based on stress. They’ll suggest he go see someone else. So, knowing that this poor guy was struggling with these demons, and then after that, hearing that he committed suicide, it was just brutal. It was a bad week for me, because it made me feel pretty helpless as an instructor. But then also, like, to know that in writing, there are clues. Cries for help or whatever. But then there’s nothing you can really do, other than be kind, and kind of push them in the right direction if they need to talk to somebody else. So, that’s been challenging.

FT: Yes, and then there’s the need to do your writing on top of that. So, to quote Nora Ephron, “The hardest part of writing is writing.” Anybody that writes can echo this in various ways. As a professor/mother of 2 living in Los Angeles, what kind of routine must you keep to write at the level that you do, and how are you able to maintain it? Do you have any great motivators/secrets that you can share on how you keep producing such high caliber work?

AM: Wow. Thanks! That’s up for dispute, but okay. I do (have some secrets). I literally go to a desert island. By myself. I'm not kidding! I will take myself to Santa Rosa Island in the Channel Islands with my backpack, my tent, and a notebook. I do! I will go out there for like three days. And there's no services. It's just a campground and a beautiful beach and trails. So I'll take my little chair and my notebook, and I’ll just go start writing. And, I feel like I'm kind of the weirdo out there, because everybody else is there in small groups. Like campers (and such). I'm like this person, like this woman, sitting all by herself. I have to! I have to get away from like Wi-fi, and…

FT: But that’s not a daily routine. How do you manage to write on a regular basis?

AM: I don't think I do it on a regular basis. I, like, binge write. I'm trying to get better at being more regular. Like, you know, just writing for 10 minutes here and there. But I'm a total binge writer. I could write for like 15 hours straight without stopping. But, yeah it's hard on the daily. I don't (write on the daily, but…). I try. I try. Yeah. Yeah!

FT: You are a woman of Mexican heritage. The University of New Mexico Press, the publishers of your book, are one of the most respected in the field of Chicana/o Studies. They took your collection of previously published essays to form your book “The Girls In My Town,” such a wonderful and eclectic group of stories that resonate with many important themes, yet through a cohesive voice. If there is one message that you would like the Chicana/o people to take from the book, what would it be?

AM: I would like it to be that there is no one experience for Latinos or Mexican-Americans. And, that there has been a lot of great writing from Mexican-American/Chicano writers, but we're all different. We all come from different socioeconomic groups in different parts of the United States. So I grew up, you know, like in the 70s and 80s in Los Angeles and I grew up as a middle class, fairly comfortable person who never had to struggle with being poor. I had other struggles, but some people have told me what I write is not “Mexican enough”. Like this (book) now doesn't count as Chicano literature (she asserts), because I don't call it that. So, I find that to be kind of sad. I don’t think that there should be any correct definition of what that should be (Chicano Literature).

FT: We are in Trump’s America, with talks of walls, deportation, xenophobic sentiments filling our airwaves, and the phasing out of DACA. What insight has teaching creative writing in the Los Angeles area given you into the perspective of the “dreamers”? Is there any particular work/merits of one of your students that stands out in your mind, and that states the strongest case for keeping DACA?

AM: I had a student, his name was Sergio, and he is a model student. He does everything right. He's on student government. He gets good grades. He played on the football team. And, he wrote this beautiful essay about that. About being brought here as a child and wanting to contribute to society, and now being against a stone wall where the country that you love, and the country that you embrace, doesn’t want a place for you. And he wrote about it so beautifully. I just felt like he could kind of be the poster-child for DACA. But, it really came through in his writing. I think he really educated the class too. About what that means, because in our class we have a lot of immigrants who came in “the right way”.

And so, I think they sometimes don't understand illegal immigrants and their plight, and like, why a person would flee from El Salvador, or why a person would come from a really poor place in Mexico and risk their lives. So they just think, Yeah, those people broke the law, and they need to wait in line just like we did. They don't understand the urgency of why people come, but I think Sergio's story really helped a lot of people to understand that DACA is not just a bunch of faceless people, but that they are real people sitting right next to you. Who we should not just have compassion for, but that we should fight for.

FT: To reference the title essay of your book, you were not one of “The Girls In Your Town.” That is, to say, a statistic of teenage pregnancy, and the largest demographic of which (in California) are Latina. I have a statistic. An article in The Fresno Bee from August 2016 states that since the year 2000, the adolescent birthrate among California Hispanics declined from 77.3 to 31.3, with “your town” of Merced slightly higher at 36.2. After discussing in your book with alarming concern (to me), the cyclical nature of the incidence of teen pregnancy and witnessing how so many of these families repeat this behavior generationally, what do you make of this statistic?

AM: Yeah! I think it’s great! But, I would say it (Merced) was kind of a culture within a culture, because in that small town it’s so common. I think a lot of girls look at other girls and they see you can have a baby when you’re seventeen. You can have a stroller and all these cute little things. And, you can have this cute little kid you can parade around the park. You have a living doll, someone to love you. I think when you grow up in a rough place like that, kind of poor, your parents, everybody’s kind of depressed. The Central Valley is kind of ugly, because it’s been so depleted by agriculture and all. I think I try to say this at the end of the essay. That, “A baby is like a thing of beauty, that you can look at as a symbol of the future”. So, it’s not all bad, but unfortunately a lot of the cycle repeats itself. You’re not the best parent when you’re 16 or 17 because you’re a baby yourself.

FT: Is it the way that society has shifted, dealing with this issue, or the way that Latino culture is moving forward (since you wrote the essay), that contributes to the decline (in that statistic)?

AM: I would love to go back and study that. Try to figure out what is accounting for that. But, maybe we're (society) doing a better job in giving teenage girls the message that there are scholarships available, a lot of alternatives. I think for a lot of kids it was like you’re either going to college or you’re not going to college. Like, you’re a smart one, or you’re a dumb one. I think a lot of teachers and counselors are getting better at showing the kids there are many alternatives. You know, like, you can go to the community college. You can take online classes. You can (also) get, not a degree, but a certificate. So, hopefully that's part of the change. (Morales ponders) Better access to healthcare. That could be. Now, if Trump has his way, God knows what will happen. Right? One thing that I was thinking of that has changed since I was there is the University of California. UC Merced is now fully established. I wonder if that makes a difference. Interesting…

FT: From reading your book, I learned the following things about you. Tell me what the following things taught you about yourself: Bowling a 274

I’m awesome! No, that was one of those things where nobody was there to witness it. So, I still believe if nobody was there to see it, and nobody was there to cheer you on, it almost, really didn’t happen. I guess the lesson is, sometimes you can do a really great thing without recognition, and you should just be satisfied with that. You should just be proud of yourself even if nobody knows about it.

FT: Encountering a mountain lion on your bicycle

AM: Ummm…that I have great…reflexes! I was so terrified when I saw those yellow eyes staring at me, that I basically disappeared. I fled the scene, but I think what I also like about that is I’m willing to put myself in dangerous places. And, I’m always proud to tell those stories because I realize you’re going to have to take risks if you’re ever really going to enjoy the world (she laughs). I saw a bobcat! Same spot. Same spot I saw this mountain lion, I saw a beautiful bobcat the other day. Standing in the middle of the road with her two babies. So, she just stopped and looked at me. Did I tell you about the grizzly bear?

FT: No, please do…

AM: I was in Alaska. I was doing this residency for Denali National Park, and they gave me a cabin to stay in for 10 days. It was 40 miles into the park, and it’s in the tundra, right. It’s a beautiful little cabin next to a river, and I had a satellite phone. They said use it if you have an emergency, you’ll contact the ranger station…which is 40 miles away, and we’ll try to get to you as soon as possible. And so, I said okay. And they said you shouldn’t have a problem. I had a car, and there was a dirt road. But, this one night, there were these windows that pull out, and you prop them open. They open this much (she gestures with her hands about 2-3 feet, plenty of room for the bear to break the window open).

One night, I left the windows propped open, and it only got dark for about 3 hours because it was summer. So, it’s like 2am-5am, it’s dark. The rest of the time it’s light. So, I’m sleeping and I hear scratching on the wall, and it’s like claws. I can hear it. It’s a grizzly bear, and it’s like, snorting! It had come out of the river, so it kept shaking off. It sounded like when a dog starts shaking off (its body) water, but imagine, like a 400 lb. dog. It was going around all sides of the cabin, and scratching, and scratching, and snorting. I had, like a can of bear spray, and the window was open, but you had to close the window from the outside. So, obviously I wasn’t going to close this window.

So, I thought, well, if he wants to get in, he’s going to get in. All he has to do is pull the window off and come in. That night, I had (eaten), like food. So, you know, I’d been making spaghetti and I have a bag of garbage by the door, and I'm like, I’m gonna die. And I really resigned myself. There’s no way I can fight this thing off, and if it wants to come in and kill me, it’s going to do it. So, I basically laid down and pulled the blankets over my head and said, I’m gonna die tonight.

It scratched like that for probably a good two hours, and then I didn’t hear anything for awhile. I thought, okay, thank God. By then, the sun was starting to come up, and the outhouse, of course, was outside. So I had to go outside. I pull the door open gently, nothing’s there, but there’s grizzly bear fur all over the wall. So, I realized what it was doing. It was scratching its back all over the cabin. It was like a scratching post, and then nails, I think, were like holding onto the wall. So, as I was taking tufts of golden grizzly bear hair, I thought, Wow, he didn’t even care about me. All this poor bear was doing was having a good ol’ time (she laughs).

It was such a weird feeling, because it was like, This is how people don’t survive in nature.

FT: What happened with the satellite phone?

AM: I never used it. I had too much pride. I didn’t wanna be like, Come help me (feigning a high-pitched, helpless voice). I looked at it, said, Should I? No, I gotta deal with this.

FT: Being uprooted without notice when your parents separated

AM: I think it taught me adults are really fucked up. Right?

FT: I can vouch for that.

AM: Because, I think that sometimes when you’re a kid, you want to think your parents have all the answers, and they’re always going to make the right decisions. But then, you realize that your parents are wrong (can be), and they might not be able to protect you, and you have to learn how to adapt to the mistakes that they make. I think a lot of kids are good at that. They just learn to adapt to their parents. You have no choice. If you’re going to survive as a kid, you have to learn to live with the rules your parents set, and the place they tell you that you have to live. Ultimately, some kids adapt better than other kids. I think that I was good at adapting though. So, I don’t have a lot of those hang-ups.

FT: Pointing a gun at your father

AM: Ah…what I learned about that is, I don’t have to put up with shit if I didn’t want to. You know, how you also think as a kid, I wish he would die. I wish he were dead. I don’t know, maybe you don’t have that experience (Morales giggles). But, I think a lot of us have that kind of flippant thought, I wish my Dad would die. But, I realized at that moment, I really didn’t want him to die. I just wanted him to go away. I just wanted him to disappear, and there’s a difference between killing someone and someone disappearing. So, I think having the gun in my hand made me understand that your life could go in different directions at any moment. It sounds kind of preachy, you know? But based on the choices we make, we go in that direction, or we go in this direction. I guess it became clear to me I didn’t want to go in that direction. Chances are, I probably would’ve fired the gun and missed, and nothing would’ve happened. Who knows? But, it was clear. I didn’t want to go in that direction.

FT: Living in a predominantly white neighborhood

AM: It taught me that I was Mexican. I’m not saying that to be silly, but I just thought for most of my childhood that I was like everybody else. That we’re all the same. I guess if I had been black, that wouldn’t have been possible (to think that way). But, because my family is fairly light-skinned Mexican-American we were kind of able to look like everybody else. But then, in that neighborhood, suddenly I’d have moments where the neighbor boys called me a beaner, and it kind of made me freeze a little bit. And I thought, Wow, nobody’s ever called me that before. It’s not like they were just saying, go away ugly. Go away you stupid girl, but they were actually calling me a name about my ethnicity. That was the first time that had ever happened. Then, I had a friend. She was my best friend, and I would go to her house. And one day, she told me her father didn’t like Mexicans. But it was okay for me to be there, because I was the good kind. So then, there were those moments that I realized that we weren’t all the same.

FT: You speak of a greater importance in the concept of heaven once you have children. In one of the essays in your book, you elegize every dog you’ve ever owned. Even though you inject a great deal of humor and folly in recounting these events, your writing is full of compassion and intelligent, moral decisions. That being said, there seems to be a connection to a serious hope for an afterlife in your work. If you get to meet your maker, what is the one thing you would ask forgiveness for?

AM: Wow! Who are you, Barbara Walters? What is this? (We share a laugh). I have so many things I would ask forgiveness for. But, I feel like I haven’t been a good family member all the time. Because, I tend to be very introverted. I like my privacy.

So, if there is a God, if I get to heaven, I would like to be forgiven for the times I removed myself from social situations. Or when during the party, went to go hide in my room. Or, not go (have gone) to see my aunt when she’s sick in the hospital. Or, the list goes on and on. I don’t think I’m like this on purpose. It’s just my personality. You try to write (and), you have to do a lot of thinking work. You have to be alone to do that. In solitude. So people don’t always understand that. They take it personally and think that you don’t like them. Or, that you’re just a bitch. So, I’d like to apologize for that.

FT: At this point, I think it is more than fair to say you’ve become a decorated writer. Your book has earned Editor’s Picks and several best book lists, you were the winner of the 2014 River Teeth Literary Nonfiction Award, the prestigious 2017 PEN/Diamonstein-Spielvogel Award for the Art of the Essay to name a few of your highest achievements. What do you feel is the most important thing you still have left to accomplish as a writer?

AM: Right now, I’m thinking I want to write short stories. I started writing fiction, and I pretty much suck at it. But, I love it. I love it! You know, like a guilty pleasure. I know that I’m not that good at it yet, but I feel that with each story that I write I’m getting better. So, my next goal is to write either a novel, or a collection of short stories and kind of cross the genre line. I still love non-fiction though. I love creative non-fiction, but I just have in my mind that I just want to write one beautiful short story. Then, I think I’ll be really happy with myself. And, what I will add, I don’t want it to be a story that feels like a true story. You know what I mean? Like it’s not just me in a fictional situation, but it is truly about another place, another time, completely different character.

FT: (Have left to accomplish) As a teacher?

AM: I want to say something practical. Like, to be better at teaching grammar. But, that’s so boring. (changes her mind) It's legitimate. I'll stick with the grammar. I think people are overlooking the importance of grammar these days. The seriousness of saying what you mean, and meaning what you say, and like, precisely wording sentences. And you know, because we text so much and we email so much, people are online all the time. And, I feel like language is getting really sloppy. So, I would hope that in the next few years, when I keep teaching, that I can really keep pounding the message in that words matter. Every word you say and write matters, and you should conserve those, and be as precise as possible.

FT: Do you want to add anything about your book “The Girls In My Town,” take a little opportunity for self-promotion?

AM: I wrote that book not knowing that it was going to be a book. So, I wrote each part of it individually, and each part led to another part of it. So, I’m proud of the fact that it feels about as natural as possible. I feel like it was written with pure intentions. Without the intention to sell it, or to write for any particular audience. I just felt like I wrote it because each of those stories was just super important to me, and I wanted to write them down before I forgot them. So, now that I’m working on a second book, I’m really struggling with, who is my audience? Why am I writing this? But with that first one, it was like…pure. And I’m very proud of that.

To learn more about Angela Morales and her work, visit her website, http://www.angelamorales.net/

Proudly powered by Weebly