- Folio No. 9

- About

- Feral Parrot : The Blog

- INTERVIEWS

- SUBMISSIONS

-

ISSUE ARCHIVE

- PRINT Chapbook No.6 Healing Arts

- Online Issue No.9

- Online Issue No.1 Fall 2016

- Online Issue No.2 Spring 2017

- ONLINE Issue No.3 Fall 2017

- PRINT Vol 72 No 2 Fall 2017

- PRINT Vol 73 No.1 Fall 2018

- ONLINE Issue No. 4 Fall 2018

- Online Issue No.5 Summer 2018

- FOLIO No.1 Fall 2018 VOTE

- ONLINE Issue No.6 Fall 2018 Fall Spirituality

- FOLIO 2 Fall 2019 Celebrating Dia De Los Muertos

- FOLIO No.3 -- Moon Moon Spring 2019

- FOLIO No.4 Celebrating New PCC Writers

- FOLIO No.5 City of Redemption

- FOLIO No.6 Spring 2020

- FOLIO No. 7 - Winter 2021 Into the Forest

- 2022 Handley Awards

- Inscape Alumni Board

- PRINT Chapbook No. 7 Healing Arts

- Blog

- Untitled

Photo by Reuters/Brendan McDermid Photo by Reuters/Brendan McDermid by Becky Nava A part of me is deeply saddened by the onslaught of individuals, namely women, coming forward with their shared experience of abuse and manipulation at the hands of men in power. Yet, another revolutionary part of me wants to dance upon the graves of these men’s careers with fierce vitriol and reckless abandon, a demolisher of patriarchal values. Why is this? Amidst these moments of female empowerment and unification lies an angry cynic that cannot resolve why it has taken so long for women to be heard. I wrestle with whether or not the recent triumphs against oppression can ignite real systemic change, as we look at more than just toppling figureheads, but continuing to work together to combat the really deep-rooted misogyny that plagues our daily lives. Many seem unnerved by the slew of allegations, though if we’re to take literature as a mirror of reality, a reflection of the social norms and mentality within its times, the institutional link between men in power and exploitative sexual violence against women has been well-documented. Voices in literature, portrayed in the characters of men and women alike, have given historical context to this malignant relationship among the sexes and societal gender roles. Yet, the imbalance of power and privilege often endowed to men, uplifted by some and condemned by others, is a constant throughout many of the classics, and this extension into our lives should come as no surprise, but should enlighten us and reinforce our beliefs in the importance of change. Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar highlights the unrealistic and exceedingly damaging effects of gender roles on the female psyche. In particular, the novel reflects on the performative facets of life as a woman. The constant need to appease others while presenting an aura of likeability and poise. Women are not allowed to be nuanced, but instead must conform to cookie cutter roles passed down from increasingly antiquated beliefs. Among them, the roles of doting wife, caring mother, and benevolent daughter - all defined by (and catering to) male convenience. To deviate from pre-established roles by ‘daring’ to focus on career or one’s self, results in immediate dismissal as cold and unfulfilled, a life of multiplicity for a woman remiss of social acceptability. And, if individual care is skewed as negative, female sexuality is punishable. This can be evidenced in Offred, the protagonist in Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale, and Hester Prynne, the infamous adulteress in The Scarlet Letter. Both women must grapple with the omnipresent expectations that promote complacency within a society, and actively work to strip away any sense of personhood. This socially ostracizing nature comes to a head in “No Name Woman”, a short story by Maxine Kingston, in which the speaker’s aunt has been written out of their family history for getting pregnant outside of wedlock. The woman is shunned by her family, her home ransacked and sacrificially ravaged by her fellow villagers. Seeing no future for her or her child, she plunges into a well, committing suicide. The man bears no responsibility in the eyes of society, he himself a victim of the woman’s sexual allure. This is a startling juxtaposition to the violence and hatred that the woman endures for the same act. The need to shame women for their sexuality also influences female self-perception, as it internalizes misogynistic values, pressuring them into casting doubt on their own experiences and emotions. The oppressive constraints of their environment or Atwood’s fictional landscape doesn’t seem quite so fictional with the ‘pussy grabbing’ gentleman occupying the White House. Or, with the existence of Roy Moore’s campaign, a Republican Senate candidate by day, and a nightmare to the countless women he has preyed upon and assaulted, not to mention the numerous legislative attacks on women’s legal, workplace, and female reproductive rights he has championed as a Justice of The Supreme Court of Alabama. In more contemporary works, Game of Thrones author George R. R. Martin has been criticized for his consistent and cruel portrayal of violence against women. It’s disheartening that we are more concerned with the symbolic portrayal of fictional women than the voices of real women. Like Dylan Farrow, Woody Allen’s adopted daughter, who in an open letter describes the abuse she endured at the hands of Allen. Yet, his films continue to be produced, his work acclaimed and awarded, as her voice withers. This begs the question, what chance do those without the luxury of her platform have of being heard? Martin’s “needless violence” comments on the means by which men have oppressed and exploited women as an excision of dominance that has been unpunished throughout history. And quite frankly, the frequency with which it appears in his work, authentically captures the experience of living as a woman in society. To exclude sexual assault from the narrative is an act of erasure, as it invalidates generations of shared trauma and oppression. Grace, by PCC’S writer in residence Natashia Deon, also maintains a heavy focus on the subjugation of women within America's post abolition Reconstruction Era, and gives voice to a grossly underrepresented and continuously exploited group - African-American women. A large facet of this struggle is related to notions of their sexuality, in which black women are stereotypically perceived to be extremely promiscuous, and as such constantly fetishized, their race reduced to a means by which to fulfill male eroticism, white males in particular. However, as women, they are also expected to comply with notions of sexual purity. These conflicting roles shape the experience of black women within the patriarchy, and shed light on the variance among women as it pertains to race. While the story may seem dated, the same antiquated gender roles make it feel more relevant than ever, as the importance of recognizing and promoting intersectionality has never been so vital. Sexual violence has never been limited to women, we must acknowledge men as victims as well. Perks of Being a Wallflower depicts the oft neglected side of sexual abuse, capturing the aftermath through the eyes of the victim, a teenage boy named Charlie. Throughout the novel, details of the abuse are murky, as Charlie’s coping mechanisms work to deny that the abuse took place. The abuser, his Aunt Helen, complicates the traumatic situation further, as familial tensions and guilt clash with gender roles that dictate the role of predator and victim. In a world in which it takes 60 women to permeate Bill Cosby’s renown, the 60:1 ratio doesn’t necessarily add up to show the progress we have made, but it does inherently reveal the value we place on male reputation. Sexual assault is exceedingly pervasive within our everyday lives, and truthfully it often manifests among those closest to us. The prevalence of rape culture, gendered stigma, and male privilege is clear. Pick up a book, flip through the channels, scroll your feed, and hints of the overarching patriarchal dictates will permeate. The medium is irrelevant if the voices cry the same fouls, but literature will not cease to echo these calls to action.

0 Comments

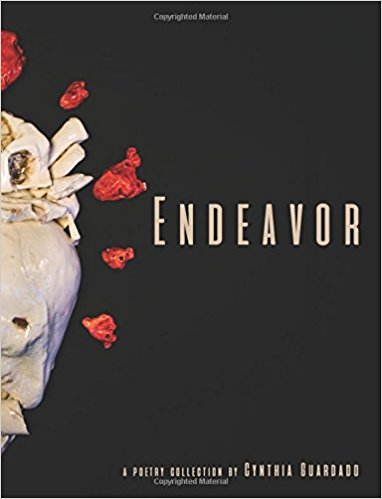

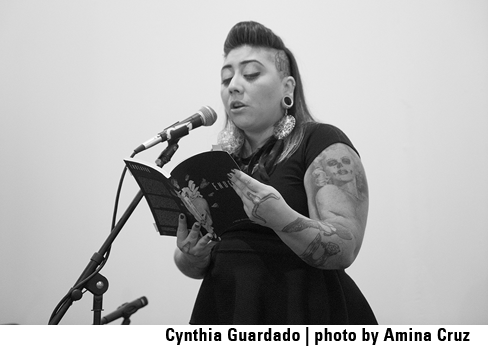

by Frank Turrisi When the Fifth Annual Poetry Day special guest author Cynthia Guardado took to the podium of the Circadian Room, the stirring academic crowd drew still. Guardado then begins to introduce her work, but it is impossible for you to take in just her words, for there is an entire persona she brings that commands your attention much more than a standard preface. You struggle to listen as you’re digesting her amalgamation of severe styles. It’s rockabilly meets chola goth with a hint of tribal warrior. She sports heavy ear ornaments with various other chunky jewelry. Starting at her hands, on both arms, are an archipelago of tattoos that morph into more intense ink sleeves before disappearing under her all black attire. More artistic ink appears in large, script letters etched on the shaved sides of her scalp, wrapping around her entire head to advertise the name of her hometown - Inglewood. I’d venture a guess there’s nobody else on the English faculty at Cal State Fullerton, or perhaps even the entire Cal State system, that looks like Professor Guardado (yes, of Creative Writing)…not even in the music departments. Then, she begins to recite her poetry in a stylized cadence, somewhat like a slam poet, and her strong, indigenous Salvadorena features combine with her make-up art and emotions to present a face reminiscent of a mask from the theatre of pain. The whole package Guardado presents works aesthetically and otherwise, but it wouldn’t if she were a poet of lesser words. Her image would only serve as a distraction, of which average words would fall short. Yet her vivid verse suits (if not transcends) her persona, punching and choking you with truth just before it caresses you into awareness. With brave clarity in her every word, Guardado relives the personal trauma she has survived and the social injustice she has witnessed in her ancestral country of El Salvador, all the while her theatrical facade hanging in the balance of shatter. She trembles as she recites, and her stylized delivery cracks as she does all she can not to let the emotions boiling underneath erupt and interrupt her intense flow. However, it is within these “cracks” that you find Cynthia Guardado’s deepest humanity, and can peer into the poet’s tormented soul. This “cracking” surfaces in a wide range of gripping poems. In one poem, she gives a unique, contemporary take on domestic terrorism. In another, she recounts the murder of her cousin at the hands of an ex-lover. She moves on to another that depicts an all too common Salvadorean occurrence, a bus bombing at the hands of La Mara Salvatrucha, alive with sounds, smells and searing images of combusting victims smashing through windows before unable to escape their burning deaths. Yet another, draws clever and powerful metaphors of white supremacy, gentrification, longstanding generational disregard for the lower class and the environment too in her factual portrayal of the events leading up to the space shuttle and namesake of her first book, Endeavor(click), being hauled through her hometown before its nearby launching (without any shortage of drama or destruction). Her POV is fiercely feminist, and perhaps even more fiercely activist, but you don’t have to view yourself as either to embrace the humanity in her work. The text of Endeavor dances back and forth from predominantly English, quite seamlessly to Spanish when it conveys more power, but it is the empathy and strong emotional connection to her words in reading it aloud that creates a language of its own. Though nobody I know could suffer the honest delivery of her words on subjects of such impact without the intrusion of tears (and Guardado is no exception), Guardado’s rockstar veneer only becomes more badass as it is pierced by what comes off as the uncontrollable revelation of her character’s duality - a vulnerable artist that stands strong in the eyes of the defeat of all of our better natures. This duality that I perceive is so much so, that during the following Q & A it also prompts a student to ask, “I noticed you read in two voices. How did you come up with that?” Guardado responds, “I read my poetry aloud when I’m editing it. I have to say the words out loud to find the rhythm. I need to hear how it all sounds together…" she goes on to describe something different than what the student was picking up on. The student seems somewhat dissatisfied with Guardado’s response. It’s because I don’t think she fully understood the question. He sits there digesting her different, still interesting, response while I imagine he's thinking, Perhaps I should’ve phrased the question differently? Am I too new to poetry to explain what I meant clearly? Perhaps she didn’t know what he meant by his question? I did. Guardado can’t possibly understand in entirety how she will exactly come off when reading to an audience. How could she? Why would she need to? This would probably make her that icky, self-conscious type - all style and no substance - and exactly what she has proven not to be, despite all of her flair. In my estimation, it wasn’t Guardado’s intention to deliver two voices, this was merely the result of her own emotional conflict bubbling under her delivery like lava. You can’t rehearse that, and no self-respecting artist would ever deny themselves the freedom of expressing that, or feeling that. So unaware of this was Guardado, she answered the young student’s question differently than it was intended. So, I sit there pretending to be Cynthia, quietly imagining a response that the student would like to hear. A response that would also be truthful. In my own rendition of Guardado’s answer to the young poetry student, I imagine saying for her: One of them is a voice that I affect as a poet and artist, to meter my verse, and to deliver the words in the way they are meant to sound. This voice makes sure the meaning of how I see the world is clear to the listener. The other voice is a deeper one that can't help but bleed through. It is the voice that has lived the words I speak, one that carries the pain of the truth, and the weight of the emotions from my experiences. I couldn’t affect this voice if I tried, and, in weaker times, I have tried to no avail. For this is the voice that must be heard. It is the voice with enough courage to keep me standing here facing my fears when I could just look the other way, pretend I am not bothered, or easily run or hide. This is the voice of the real me. That is exactly what I saw in Cynthia Guardado’s work. That is how she made me feel. We all applaud Guardado, the lone guest author invited to speak in this year’s Poetry Day format. Now, it is on to the many students that raised their hands when asked if this was their first time attending any poetry event. It is their turn to gather their voices and take the words of their experience to the open mic. PCC’s 5th Annual Poetry Day was organized by Professors Emily Fernandez and Ekaterini B. Kottaras of the English Department. It is an event held in celebration of Poetry Month (April). This year’s event was geared toward a multilingual theme. In addition to the usual poetry classes in attendance, language classes were also invited for the first time. All students in attendance were encouraged to present poetry in their language of choice (if not, native tongue). By inviting only the multilingual Guardado to read, as opposed to several authors in past formats, the 2018 Poetry Day was designed to allow more time for students to share the open mic. |

IMPORTANT NOTE:

PCC Inscape Magazine, housed at Pasadena City College, is following Coronavirus protocols. At this time our staff continues to read submissions and publish web content. Note:

Blog Posts reflect the opinions of the writer and not the opinions of Pasadena City College or Inscape Magazine Editorial Staff Members. Archives

December 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed