- Folio No. 9

- About

- Feral Parrot : The Blog

- INTERVIEWS

- SUBMISSIONS

-

ISSUE ARCHIVE

- PRINT Chapbook No.6 Healing Arts

- Online Issue No.9

- Online Issue No.1 Fall 2016

- Online Issue No.2 Spring 2017

- ONLINE Issue No.3 Fall 2017

- PRINT Vol 72 No 2 Fall 2017

- PRINT Vol 73 No.1 Fall 2018

- ONLINE Issue No. 4 Fall 2018

- Online Issue No.5 Summer 2018

- FOLIO No.1 Fall 2018 VOTE

- ONLINE Issue No.6 Fall 2018 Fall Spirituality

- FOLIO 2 Fall 2019 Celebrating Dia De Los Muertos

- FOLIO No.3 -- Moon Moon Spring 2019

- FOLIO No.4 Celebrating New PCC Writers

- FOLIO No.5 City of Redemption

- FOLIO No.6 Spring 2020

- FOLIO No. 7 - Winter 2021 Into the Forest

- 2022 Handley Awards

- Inscape Alumni Board

- PRINT Chapbook No. 7 Healing Arts

- Blog

- Untitled

|

by Laiya Tanedo

Harryette Mullen is the author of several poetry collections, winner of a PEN Beyond Margins Award, National Book Critics Circle Award, and a finalist for a National Book Award. She teaches American Poetry, African American Literature, and Creative Writing at UCLA. Harryette Mullen writes "We Are not Responsible" (pg. 136 ‘of poetry and protest’) in the language employed by corporations, authority officials, lawyers, and bureaucracies. She especially makes use of the legal jargon used to issue disclaimers and limit liabilities. She reveals how the language that is designed to be benign can, in fact, sound inherently cold and deceitful. In her bio, Mullen says, “Like music and other arts, and even spiritual practice, poetry is what reminds me that I am human. A dog doesn’t need to be reminded that it’s a dog, but I think occasionally we human beings need to be reminded that we are human” (Of Poetry and Protest, pg. 135). However, this value of intimate interpersonal connection is in stark contrast with the verse of Mullen’s poem “We Are Not Responsible” to follow. Every line in this verse begins with the phrase ‘We’ and is then followed up by authoritative restrictions. It is possible to take a knife and slice the first three syllables of each line into a neat chunk of negatives. ‘We are not', 'We can not', 'We do not’, and ‘We reserve’, as if changing the format slightly each time will obscure the fact that this authoritative ‘We’ is denying us access to something. We are not responsible for your lost or stolen relatives. We cannot guarantee your safety if you disobey our instructions. These first few lines are so familiar, every modern human being has had to acclimatize themselves to these monotone voices- in airports and on phone calls with robots. The english is pristine and unintrusive, but Mullen has changed the vocabulary at the very end - making a reader feel a lurch in regularity. Dread begins to build, because a reader only witnesses the tone shift at the end of the sentence, as if having a delayed realization that they might be about to lose something important. Mullen is clever in her following introduction of implied aggression. We do not endorse the causes or claims of people begging for handouts. We reserve the right to refuse service to anyone. The last line of this verse is powerful, it is made all the more painful to the reader because the language of this is completely unchanged from its original context. It is still incredibly commonplace to see these signs in restaurants and airport terminals. This last stanza plays as a list of rules and regulations - uniform, and always ending on the down beat. Mullen hooks the reader, and her bridge into the next stanza merely goes into greater detail - while raising the stakes of the previous situation. Your ticket does not guarantee that we will honor your reservations In order to facilitate our procedures, please limit your carrying-on. Before taking off, please extinguish all smoldering resentments. If you cannot understand English, you will be moved out of the way. In the event of a loss, you’d better look out for yourself. Your insurance was cancelled because we can no longer handle your frightful claims. Our handlers lost your luggage and we are unable to find the key to your legal case. Mullen explains, “In a general way it’s about the social contract. The borrowed language in the poem runs the gamut from airline safety instructions and corporate disclaimers to the Supreme Court’s ruling against Dred Scott. This was written before 9–11, when profiling was widely accepted as necessary for security. Yet, even before that terrorist attack, racial profiling targeted people of color as potential criminals, like the '99 police shooting of Amadou Diallo. We that consider ourselves law-abiding citizens have surrendered a lot of our freedoms in order to feel safe. The poem plays back the language of authority in what seems to me a logical movement from the rules and regulations we must obey as airline passengers, to the whole system of laws derived from original documents securing personal property of mostly white male owners. What might be unnerving when I read this poem to an audience is that I keep repeating the word “we”. Instead of “us" and "them” it’s “we" and "you,” so it’s a bit skewed when I speak in the voice of the authoritative “We” versus “You” whose rights are threatened or violated.” - Harryette Mullen, Jacket Magazine You were detained for interrogation because you fit the profile. This line both builds tension and serves as a bridge, maintaining the notion of individuality being compressed into a file, and adding to the emotional detachment of the "rules". You are not presumed to be innocent if the police have reason to suspect you are carrying a concealed wallet. It’s not our fault you were born wearing a gang color. It is not our obligation to inform you of your rights. These last 3 lines are the first explicit mentions of police interactions with people of color that led to violence, and because Mullen still utilizes ‘You’, the reader’s experience of the poem is sharpened and specific. The reader is the minority, and ‘We’ includes enforcers, most likely with loaded guns. The intensity of this imagined experience serves as the perfect final bridge into the last stanza. “Step Aside” is the last 3 syllable entrance into a line, and it is a powerful one. This line cannot be used anywhere else in the poem, it brings proximity with the danger that the reader is perceiving- it brings the officer up close and personal. This claustrophobic experience brought to the reader could not exist without all the set up of the previous stanzas. Step aside, please, while our officer inspects your bad attitude. You have no rights that we are bound to respect. Please remain calm or we can’t be held responsible for what happens to you. As one looks back over the poem, realize two things. If you count syllables, you realize that almost every line is made up of an even number of syllables. This is a trick of rhetoric, of public speakers of every kind, because the human mind wants to believe that a sentence that sounds well balanced also has well-balanced logic behind it. This is why the catchiness of slogans is so important. This is why a man can get off a murder charge when his lawyer insists, “If it doesn’t fit, you must aquit!” Yet, this is directly contrasted by the blatant aggression and underlying threat of this poem. The last line, “Please remain calm or we can’t be held responsible for what happens to you,” is 19 syllables long. It steps out of formation, violent yet distanced from the violence. As if those who enforce the rules bear no responsibility. As if the law is never wrong. Harryette Mullen brings to mind that when we hear or read all these disclaimers and jargon - perhaps, this is what corporations and governments are really trying to say. This use of language is not dissimilar to the inhumane language used in WW2 to describe an enemy. Perhaps, they develop this language specifically to separate them from ‘us’, the law-abiding citizens who rely on them. Perhaps, they build their words and actions to be as robotic as possible, because ‘We’ could not bear to continue to do what they do to ‘You’ if they related to ‘You’ like a fellow human being. In other countries it is commonplace for strangers to call each other ‘uncle’, ‘auntie’, ‘grandfather’, ‘brother’, ‘sister’, and ‘child’. What would happen to the rate of police brutality if they were required to call citizens by informalities? “Put your hands up, Auntie”? Well, that sounds ridiculous. How about, “You’re under arrest, brother”? It sounds laughable - a line from a B-movie. Yet, can you really imagine a police officer being able to thoughtlessly use excessive force on another young black male, directly after calling him ‘Son’? Laiya Tanedo is an English Major at PCC and a guest blogger for Instress. Laiya's artwork is also featured in the Inscape Online, Vol. 2, Fall Issue. References Cushway, Philip. “Of Poetry and Protest: From Emmett Till to Trayvon Martin”. W.W. Norton & Company, Inc, 2016, pg. 136. Lancaster, Simon, and TEDxVerona. "Speak like a Leader TEDxVerona." YouTube. YouTube, 22 May 2016. Web. 27 May 2017. Mullen, Harryette, and Barbara Henning. “Harryette Mullen: From S to Z.” Jacket 40 - Late 2010 - Harryette Mullen: From S to Z: Harryette Mullen in conversation with Barbara Henning, Jacket Magazine, 2010, jacketmagazine.com/40/iv-mullen-ivb-henning.shtml. Accessed 27 May 2017.

6 Comments

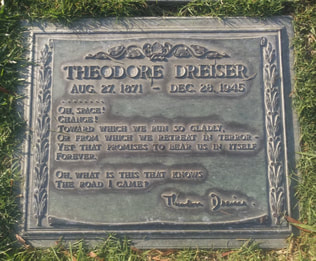

by Kathlene McGovern I’ll confess it: I love a good graveyard. Old, overgrown, well-manicured, stately… behind a church or on a hillside; I don’t care. I’m happy to have a long wander around. The grounds teem with people’s stories – heartbreak and hope, staggering successes and unfulfilled dreams. And, for all the writers reading this, it’s an amazing place to find names for your characters… Grover T. Garland… Wallace Albright… Kit Cardy… and no, you can’t use any of those – I already have. I’ve always been a fan of Forest Lawn in Glendale. I’ve walked the labyrinth that’s a small replica of the one that covers the vast floor in the Cathedral at Chartres; stared at the Wee Kirk O’ The Heather chapel while pretending to live a far more interesting life in some idyllic Irish village; visited the Forest Lawn museum and seriously contemplated buying the Mother Mary nightlight in its uber-tasteful gift shop. So, when deciding to explore the “haunts” of writers who made their careers and lives in the Los Angeles area, I immediately wondered which of them had chosen Forest Lawn as their last address in town… L. Frank Baum of Wizard of Oz fame; Louis L’Amour whose western short stories and novels were made into films and TV series along with Edward Curtis and Robert Maupin Beck. But the writer with the most literary street cred was Theodore Dreiser, a journalist cum novelist whose most famous works include Sister Carrie and An American Tragedy. Dreiser is considered by many the “father of American realism,” a 19th century movement that called for the depiction of contemporary social realities which allowed for a more accurate portrayal of American life in literature. Dreiser was a Nobel Prize in Literature nominee in 1930. This being L.A. and all it’s incredibly easy to celebrity stalk someone -- even the dead – so I set my course to find where Dreiser left his mortal coil when he went to meet his great reward. Two websites later I found that he was located in the Whispering Pines section of Forest Lawn “… just past the Finding Moses fountain… at the top of the hill… lot 1132.” Early Saturday morning I skulked along the cemetery’s steep incline, slick with dew, hoping I didn’t roll down the hill and land with a splash next to marble baby Moses. I’d have totally felt bad scrabbling for purchase over people who’ve paid market value to find a little peace and quiet except I’ve witnessed families having full-on picnics complete with wine, cheese and assorted charcuterie atop their loved ones’ remains myriad times, so I figured a little detective work couldn’t be that offensive. Finally, I made it to the top of the hill and found… them. Not just Theodore Dreiser, but next to him Helen Dreiser, the woman he married in the last year of his life after a twenty-five year relationship during which he had many other affairs with many other women.

In a May 18, 1930 interview featured in the Dallas Morning News, writer Vivien Richardson quotes Dreiser on women: “Many a woman is holding down a job for which some man gets credit.” “Women have been virtual rulers for a long time.” “Why not a woman president? I’d vote for her and probably ask her for a job afterward.” We all know writers as a breed are complex, and Dreiser was no different. While championing the idea of women in power, on a personal level, Dreiser’s relationships with women were far more complicated. Married for the first time in 1898, he had countless affairs and relationships even after meeting Helen, who beginning in 1919 would be his constant companion for the next quarter of a century. Knowing this, Dreiser’s description of the first encounter of his name character in Sister Carrie, Carrie Meeber and the man who would change her life, Charles H. Drouet, becomes even more poignant… “How true it is that words are but vague shadows of the volumes we mean. Little audible links, they are, chaining together great inaudible feelings and purposes. Here were these two… both unconscious of how inarticulate all their real feelings were.” As I sat on a marble bench looking out at the incomparable views Forest Lawn provides, I wondered about the woman who lay next to Theodore Dreiser. The sort of love that made her stay; the sort of grace that drove her to dedicate her memoir, My Life with Dreiser to: “the unknown women in the life of Theodore Dreiser who devoted themselves unselfishly to the beauty of his intellect and its artistic enfoldment.” The sort of talent and heart that allowed her write the poem that serves as the epitaph on her grave marker printed in part here… If I did touch that margin of your soul In its swift moving earthly seeming flight, That shed a brilliance to the inner sight And opened up the windows of the mind To rarer beauties far than most men feel: Then I have sung the lark’s sweet song designed To fuse our senses with celestial seal Instead of wondering, I began a search on Helen and whether it’s a commentary on how she lived, or on the society in which we currently live, aside from her now out-of-print memoir, her name, when entered into any search engine lead only to an expanse of information about her husband. |

IMPORTANT NOTE:

PCC Inscape Magazine, housed at Pasadena City College, is following Coronavirus protocols. At this time our staff continues to read submissions and publish web content. Note:

Blog Posts reflect the opinions of the writer and not the opinions of Pasadena City College or Inscape Magazine Editorial Staff Members. Archives

December 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed