- Folio No. 9

- About

- Feral Parrot : The Blog

- INTERVIEWS

- SUBMISSIONS

-

ISSUE ARCHIVE

- PRINT Chapbook No.6 Healing Arts

- Online Issue No.9

- Online Issue No.1 Fall 2016

- Online Issue No.2 Spring 2017

- ONLINE Issue No.3 Fall 2017

- PRINT Vol 72 No 2 Fall 2017

- PRINT Vol 73 No.1 Fall 2018

- ONLINE Issue No. 4 Fall 2018

- Online Issue No.5 Summer 2018

- FOLIO No.1 Fall 2018 VOTE

- ONLINE Issue No.6 Fall 2018 Fall Spirituality

- FOLIO 2 Fall 2019 Celebrating Dia De Los Muertos

- FOLIO No.3 -- Moon Moon Spring 2019

- FOLIO No.4 Celebrating New PCC Writers

- FOLIO No.5 City of Redemption

- FOLIO No.6 Spring 2020

- FOLIO No. 7 - Winter 2021 Into the Forest

- 2022 Handley Awards

- Inscape Alumni Board

- PRINT Chapbook No. 7 Healing Arts

- Blog

- Untitled

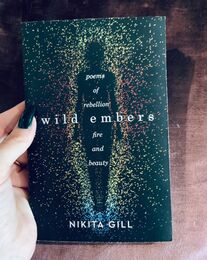

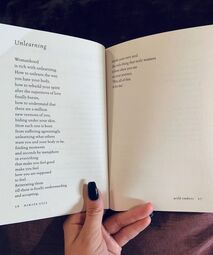

Written by Cassie WilsonSomebody once told me that my face was the prettiest thing about me. That my body wasn’t enough. Somebody once told me that if I worked out a little more and ate a little less I could be pretty enough. But enough for what I asked myself? Somebody once told me that losing the weight would be the greatest accomplishment of my life. That if I shrunk myself down to smaller size that I would float across the street with a god like happiness that would burst out of my body, sun rays that hit windows with reflections of rainbows and light on a warm summer's day. And I asked myself how being smaller could amount to such a feeling? Somebody once told me that being fat was my worst characteristic. That my stretch marks were flaws etched into my skin as a remainder of why I wasn’t worth it. And I wondered to myself how being fat, could be the problem? Somebody once told me that when I lost the weight everything else would melt away like honey in hot tea and I would be happy. And so when I lost the weight and the weight in my head still pressed hard like mountains of snow inside a blizzard I wondered if maybe I just hadn’t lost enough? Somebody once told me I just needed to tone some more and lift some weights and loose the excess around my waist, that would do it. I could be happy. So when I shed the pounds and built the muscle and still the weight in my head pounded like bricks in concrete being set in stone not able to lift from place, I wondered, if maybe my body just wasn’t built for warm summer days? After I lost the weight I was left with a version of myself I didn’t recognize. I found myself inside my bathroom, feet against chest, ready to unlearn all the parts of myself that shrunk me. For my birthday last year I was given Nikita Gill's book, Wild Embers, poems of rebellion, fire and beauty. Gill writes about the the process of "unlearning", how to dig yourself back up from the rubble of your own making, from the self negative statements and all the somebody's who told you you weren't worth it. In Nikita Gill’s poem, “Unlearning”, she writes: "Womanhood is rich with unlearning. How to unlearn the way you hate your body, how to rebuild your spirit after the supernova of love finally bursts, how there are a million new versions of you hiding under your skin.” When Gill references the "supernova of love" that bursts and beams, she is talking about the breaking point. The knees against chest, the aftermath of a self critical crock pot, the main ingredient: self-loathing. She refers to this moment as a burst of love because when you hit this point, the point when you just can't go on any longer, it's the moment you say to yourself: I chose me, because I matter. And that is the first time in a series of self destruction that you chose yourself instead of your crock pot. When I stopped listening to somebody’s and just finally chose me, that promised god like happiness that bursted and beamed and made me float, came and I was shocked to find it wasn’t from losing the weight. At 23 years old the greatest accomplishment in my life was gaining and not losing. Gaining love and acceptance and forgiveness and I feel heavier and I am worth it. It took me a year and a half to lose the weight and I ended up losing what made me beautiful to begin with. I lost the passion I had for writing and the way I loved the freckles on my skin and the curls that dance on my shoulders. I lost the smile that used to light up my face when I laughed and how I could dance and not care if my body moved with a fierceness that was not afraid to take up the space that I deserve. So when I sat with myself a sum of a number lighter I realized the only weight I needed to loose was the hate and shame and self loathing that society's somebody's had mounted on me like rider against horse, guiding me to all the wrong places. And I asked myself why I ever started listening to somebody’s. Gill writes, “How each one is born from suffering and agonizingly, unlearning what others want you and your body to be, finding moments and seconds by metaphors in everything that make you feel good make you feel how you are supposed to feel.” When Gill writes that some of the best parts about ourselves are "born from suffering and agonizingly" she is referring to the parts about us that learned to stand up and fight. To choose our own warm summers days. The prettiest thing about me was never my face and fat is not an insult. Fat is a word used to try to discredit the amount of space a woman deserves to take up. I am enough and so is every other woman ever called fat because fat is and never will be a negative aspect of what makes up a person. Since when did fat become a word thrown around to discredit a person’s soul and spirit and wholeness. What others want me and my body to be is not a problem, but a note to be thrown in a suggestion box of nobody gives a fuck. My god like happiness came from my “feel good metaphors” that were and are warm cookies in bed and a chocolate milkshake after dinner and me telling me and anyone else: I am here, I am enough, and I will not shrink the space in this universe that I deserve. Gill finishes her poem writing, “Reiterating them till there is finally understanding and accepting, inside your very soul the only thing that truly matters is how often you say on your journey, ‘This, all of this, is for me.’” This life is mine and I will never apologize for taking up more metric units again because the problem was never the number. The prettiest thing about me is and will always be all the things that make me heavy. My stretch marks etched in my skin are my triumphs over hardships and the nights I spent unlearning the parts of myself that told me to listen to somebody’s. My waist encompasses the length I’ve spent working on me, for me, because I matter. My weight will never define my self worth and fat will never be an insult. When Gill writes, "This, all of this, is for me" she is referencing this journey of life for the individual. It is personal and unique and important and yours. How you live your life, learning or unlearning, is all your own, there isn't a need to take suggestions from bystanders who think their suggestions could amount to the absolute beauty that is your spirit and soul. So the next time somebody tells me I am fat I will thank them for their consideration in noticing the home I’ve built for myself in a body that carries my spirit and soul. Cassie Wilson is a student at Pasadena City College majoring in English. She says, "I won't ever stop talking about the relationship between ourselves and our bodies. It's such an important topic and I hope that with my own experience I can create or inspire some positive change in the way we treat, talk, and view our bodies."

1 Comment

Written by Jiarui Ye A Photo by Jiarui Ye A Photo by Jiarui Ye The air tastes like salt and sweetness. Walking in the dry air of Southern California usually gives me a strong urge to sneeze from the pollen (thank you, spring), but not today. When someone asks what I think of the term, desert, it can sometimes be deferred to thinking about someplace similar to this one. I find that interesting, since we have plentiful water in the city. However, heading more inward into the state, the more we see a change in scenery and suddenly, this place is no longer the City of Angels but rather, the City of Death, more specifically, Death Valley. I had begun my journey in Pasadena, California, and head onto the 134, to get to the 110. I soon switch gears, heading North on the 14 freeway, passing through Palmdale and the famed Red Rock Canyon Park. 90 miles later, I split off near Red Rock Canyon Park to head into deeper forest for the reaming 70 miles. Once I arrive, it's quite an ordeal to get inside. There are no gas stations in sight, an act of kindness to the trees, protecting them from fire hazards. The looping trail is long and windy, tourist destinations at every stop. There is so much majesty in this place. (If you prefer not to drive, there is a great shuttle service that takes you through this trail.) And then, there, in the middle of the desert, I see an amazing salt reserve. I was shocked —this was the Badwater Basin. A major facet that draws much attention to Death Valley. The scenery is amazing. For those of you who don't know what a Badwater Bain is, imagine a world of snow but with no ice. White landscape - but no water in sight. I begin to feel deeply connected to nature while in this Death Valley place and I think of the novel, “The Desert,” by John C Van Dyke. These majestic views are what make the connections between Western society and depopulated utopian. Throughout the novel, there is no mention of different individuals; no one is separated from nature, instead they are nature: “It’s just him with his art connoisseur’s eye and the shifting sunlight across the desert landscape.” The possibilities of what a Western desert could do opened up the possibility of of its beauty. The elements of Death Valleys are changed by this and the lush picturesque background is holds is discovered. Contrary to typical sand dunes, the Badwater Basin is a beautiful white sea that draws individuals in like bee to honey. The long winding roads of the desert lead to nowhere and are filled with the sandy remnants of eroding rocks. Twisting round and around, the roads are a symbol of the convoluting decisions in our lives surrounding us, but inside - only peace. From the world’s lowest point to the beautiful white pools that litter around the hiking paths, many people - including myself - are filled with child-like awe. The scenery assimilates into the natural background and it is so hard not to stop and bask in the beauty of the Basin. Traveling to these places provides something that city life cannot: the welcome of salt to an open wound. The welcome of this Badwater Basin into the deepest parts of ourselves - the love and the hate - the interconnectedness of it all - and finding yourself stripped beautifully raw with openness, all from the salt and sweetness. Jiarui Ye is a travel writer and a student at PCC majoring in business and finance. She says, "She enjoys theology and politics when she isn't traveling or taking photos."

Written by Kaylin TranCommunity; noun, often attributive com·mu·ni·ty | \ kə-ˈmyü-nə-tē \ Definition:

// the international community

Clifford Larson’s short essay is one of the more rare finds in Inscape’s recent issue of the 2019 Fall Common Book—it certainly stands out amongst the other skillful works of poetry and short fiction. “California Sensibilities” is a bittersweet piece about Larson’s personal experience moving across the country intertwined with references to Helena Viramontes’, Under the Feet of Jesus, a book about a migrant family working in California, and a quote from writer and scholar David Ulin, "thinking about California is thinking about struggle, and a sort of 'brothers in the ranks' while enduring the struggle." Having been uprooted from South Boston with no warning, he struggled with his solo move to southern California. His writing is eloquent yet simple, casual, and honest; it’s an entirely relatable piece with a certain amount of finesse that elevates his style of writing. He describes how he “literally showed up to California with $4 in [his] pocket” and had to survive off the free meals he received at work—three months’ worth of sushi, to be exact—to get back on his feet. Ironically, it was because of his struggles that he was able to survive, some might even say succeed. His grit, his determination to survive in a foreign environment consequently lead him to discover that his co-workers were enduring similar hardships. He’d met other people who were California transplants from Mexico, Canada, Europe, Russia, etc., “but all of us [were] in California because of the possibilities we’d imagined.” In reference to Ulin’s idea of the California struggle, they endured it as “brothers in the ranks,” much like how the migrant workers in Viramontes’ novel had to develop trusting relationships to survive their hardships together. The parallels between Larsen and the migrant workers reveals how universal and necessary a sense of community truly is. Larsen isn’t Latino or Hispanic, but he still relates to their struggle to survive. It takes more than hope and ambition, and it certainly takes more than self-motivation. It’s important to establish connections with others, to develop a sense of camaraderie amongst the strangers who become your family. It’s about creating a community with a group of people who make you feel like you want to succeed, not that you have to. This is what Larsen attempts and properly communicates in his short essay. The universal message of connection and support is what he and the migrant workers needed for future success. He mentions the startlingly bittersweet reality of his situation: “I knew that someday I’d get out, but like Viramontes’ characters at the end of her book, there’s no telling what will happen to them. There’s hope, yes, but sometimes that’s not enough.” It’s this struggle that truly represents the Inscape branding and aesthetic, the message that our publication strives to capture. “Inscape is the unique inner nature of every thing and every person: the eclectic, the human, the becoming, and the unexpected—a compost of imagination and inquiry.” Larsen’s story is a shared part of the human experience. It’s human nature to have a sense of belonging, to want to succeed. His candor exposes the raw reality of what it’s like to struggle. More importantly, he emphasizes that it’s a widely-shared, universal concept that anyone and everyone has a shared understanding of. Moreover, he becomes a transformed individual; his confidence and self-realization blossom after he finds the strength to become something greater than what his provided circumstances would have entailed. He embraces the unexpected—his sudden move to California, the similarities between him and his co-workers—and manipulates them to become his successes. His determination to succeed propelled him, but his community is truly what gave him the strength to prosper. “We need each other—we need a community. In a sense, I’ve found a community in these books.” Kaylin Tran is a journalism major at Pasadena City College. She is the assistant blog editor for Inscape as well as a staff writer for the PCC Courier. She hopes to work as an editor at a digital magazine.

Written by Jiarui Ye A Photo by Jiarui Ye A Photo by Jiarui Ye Beauty is in the eye of the beholder. As a resident of Southern California, I am quite familiar with the feeling of the sun beaming against my back, the sound of crashing waves, and the smell sea air. The clear oceans bring serenity and peace to even the most boisterous of characters. Big Sur has long been known as a romantic tourist destination where millions flock every year. With uniquely-placed boutique hotels and lush forest greenery, it is the crown jewel for residents who are looking for a calming getaway. The symbolic view of Big Sur is the McWay Falls; just around the bend off the 1 freeway. The sweeping tones of blue and green are majestic, if not iconic. Getting to the incredible landscape will not be an easy journey, 287 miles stood before me and McWay Falls. I first start off at the PCC campus and head onto the 101, heading west towards the Californian shore. 103 miles later, I am shifted into the natural scenery of oceans and beaches and as I turn onto the 101, I am reminded why I love these drives. The next 56 miles of the 101 freeway is the commitment of me and the ocean. In the middle of Julia Pfeiffer Burns State Park, I park on the side of the road, ready to hike the short walk for the waterfall views. Trailing along the rickety wooden steps, I am suddenly reminded of the novel, "Daring to Dream" by Nora Roberts, and the homey feeling that Margo, the protagonist of the book, feels when she smells wet algae and salt; the reminder of her home in Big Sur. Even though Margo has strayed far away from her family and ventured out to Europe to chase her dreams, she returns. Margo is welcomed as a member of the family and sister to young Laura and Josh Templeton, as well as orphaned cousin Kate, who grows up with them in the lap of luxury. The feeling Margo experiences, heading to a place of sanctuary, is nostalgic of how I felt in that exact moment. Big Sur’s fleeting population of incoming and outgoing visitors makes dreams come true. Despite the beautiful scenery, I could not help but think of hitting rock bottom. As I stared down a daunting cliff, I realized that when you fall, there is no other way but up. Margo’s journey represented that for me. Margo has dream of becoming a lush model, but soon saw those dream dash and divide in front of her. She had hit her rock bottom and as she rushes home, the trials and tribulations of her life flash before her. She realized that there are different type of goals in her life, different types of success. Modeling wasn't her only way forward and with this she rebuilds herself up from the bottom. Growth and acceptance equate to finding your serenity. Big Sur is not only a place where people come for weekend getaways or romantic mountain moments. Its legacy is in the generations of people- including myself- who come to laugh, to love, to cry, to heal, to find themselves again. Not ready to say goodbye? Come back next week and see where Jiarui takes us next in the last blog of this special 5-part travel blog series! Jiarui Ye is a student at Pasadena City College majoring in business and finance, with a flare for travel writing.

Written by Jennifer LopezJennifer talked with Michelle Rosado in May 2019 and created this collage-style mini-profile from their conversation. On the writing process and what makes a powerful poem: Rosado says: a poem is primarily derived from its power and strength. It is based on the ability to create a meaningful metaphor to fully capture those memories, wishes, and personalities that the writer possesses. On what influences and inspires: Most writers are inspired by experiences that shape us. Rosado said she was very much influenced by the experiences of her childhood. Her book Why Can´t It Be Tenderness is a filled with poems and writings about her childhood and about her adult life. Reading about her childhood experiences really inspired me to look back on some of the experiences that I faced growing up. For instance, Rosado felt she had a different connection to her mother when compared with her father. In one of her poems she reflects on the need to rely more on herself. This made me think of being in solitude and comfort with one’s self. Fun Facts about the Author Rosado describes herself as a snail emoji. She relates more to her mother now that she’s grown up. Recently she has been seeing more and more butterflies everywhere she goes. Many of the people Rosado works with are writers or have some association with art and writing. Learn More: Visit the website: http://www.michellebrittanrosado.com/ Buy the book: http://www.michellebrittanrosado.com/books Read other interviews: http://www.michellebrittanrosado.com/interviews Read a few sample poems: http://www.michellebrittanrosado.com/poems Jennifer is a student at Pasadena City College and former member of Inscape.

|

IMPORTANT NOTE:

PCC Inscape Magazine, housed at Pasadena City College, is following Coronavirus protocols. At this time our staff continues to read submissions and publish web content. Note:

Blog Posts reflect the opinions of the writer and not the opinions of Pasadena City College or Inscape Magazine Editorial Staff Members. Archives

December 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed