- Folio No. 9

- About

- Feral Parrot : The Blog

- INTERVIEWS

- SUBMISSIONS

-

ISSUE ARCHIVE

- PRINT Chapbook No.6 Healing Arts

- Online Issue No.9

- Online Issue No.1 Fall 2016

- Online Issue No.2 Spring 2017

- ONLINE Issue No.3 Fall 2017

- PRINT Vol 72 No 2 Fall 2017

- PRINT Vol 73 No.1 Fall 2018

- ONLINE Issue No. 4 Fall 2018

- Online Issue No.5 Summer 2018

- FOLIO No.1 Fall 2018 VOTE

- ONLINE Issue No.6 Fall 2018 Fall Spirituality

- FOLIO 2 Fall 2019 Celebrating Dia De Los Muertos

- FOLIO No.3 -- Moon Moon Spring 2019

- FOLIO No.4 Celebrating New PCC Writers

- FOLIO No.5 City of Redemption

- FOLIO No.6 Spring 2020

- FOLIO No. 7 - Winter 2021 Into the Forest

- 2022 Handley Awards

- Inscape Alumni Board

- PRINT Chapbook No. 7 Healing Arts

- Blog

- Untitled

Written by Cassie Wilson

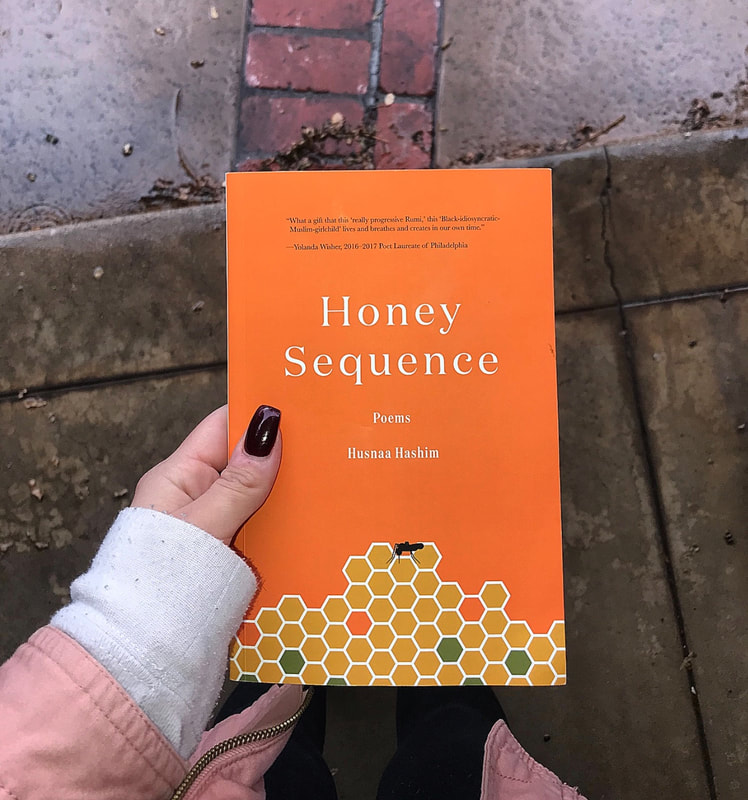

Husnaa Hashim. Honey Sequence. Poems. 33pp. Free Library of Philadelphia; The Head & The Hand. $10. theheadandthehand.com

The first time I was asked to locate and identify “the lesbian girls of grade 12” I was 14 years old. I was dressed in dark blue Dickie shorts that read: I am conformed. I was dressed in a black V neck sweater with a label on the right that read: I am invisible. I was dressed in a white collared shirt up to my neck that read: I am only straight. I was 14 years old when I was asked to guide my English Literature teacher to the exact location of “the lesbian girls of grade 12” so that she could hand them a red-inked slip for the detention of loving a woman while being a woman. I guided her to the small gym structure in the front of the school where “the lesbian girls of grade 12” stood. She thanked me for my cooperation.

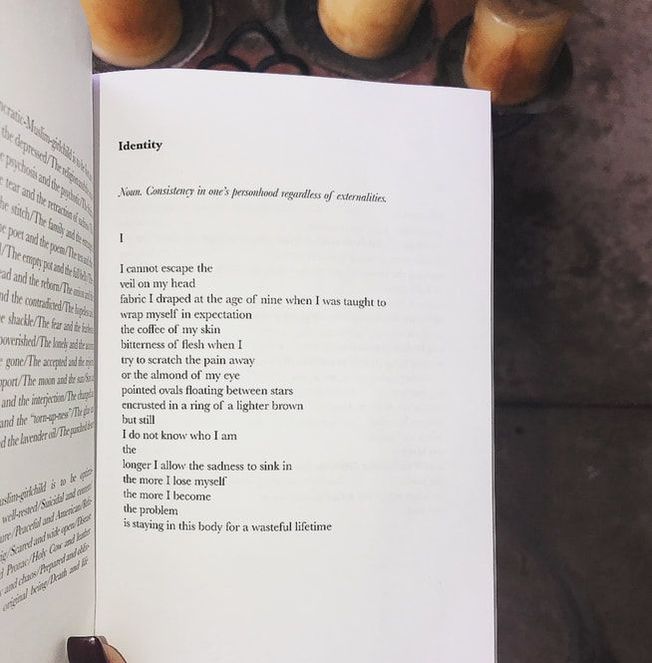

Three and a half months later my same English Literature teacher found me in the front of the school in the small gym structure where now “the lesbian girls of grade 9” stood. She handed me a red-inked slip for the detention of me, a girl, confessing my love for another girl. The same echoes of gratitude for my "cooperation" muffled around me as I stood before her. Being a Catholic and identifying as gay in a private school, a school devoted to shrinking the idea of individuality amongst the students, was challenging. My sexuality was constantly punished with red ink. Similarly, Husnaa Hashim illustrates her own struggle for the duality in her identity as a “Black-idiosyncratic-Muslim-girlchild” in her new chapbook, Honey Sequence out this month from The Head & The Hand press as part of the Free Library of Philadelphia project. Husnaa Hashim is the former Youth Poet Laureate of Philadelphia. She is a student at the University of Pennsylvania and has been writing for over 8 years. She has placed 1st in the Free Library Teen Poetry Slam, received the American Voices Medal award, 4 Gold Keys, 6 Silver Keys, A National Gold Medal, and various Honorable Mentions from the Scholastic Art and Writing Awards. In her free time she finds joy in creating flower crowns and relaxing with her feline friend, Maya (Angelou) Luna. In her poem "Identity", Hashim’s expresses the challenges she faces as a young, Black, Muslim, Woman. She writes: I I cannot escape the veil on my head Fabric I draped at the age of nine when I was taught to wrap myself in expectation She was taught from a young age to wrap herself in a Hijab, a veil used to cover the head, which represents in Islamic culture, female modesty in the presence of a male. Hashim feels trapped in the expectations set by her religion when she expresses "I cannot escape the veil on my head". She struggles with accepting this sacred tradition as apart of her identity as an individual or as apart of her religion and culture. Reading this poem, I felt an immediate kinship. I was brought up Catholic all my life. I was enrolled in Catholic private schools. I was an active member of the church. I served as a rosary reader, lecturer, and altar server, yet, none of that seemed to matter because of my sexuality. In the Catholic religion, being gay is a sin. I believed in my Catholic faith, but I also knew I was a Lesbian. I grew up being gay, this was not a choice, but a part of the fabric of who I am. The expectations that my religion forced onto me was difficult to escape from, just as Hashim struggles to escape from the expectation set by her own religion. Four months into my freshman year of High School, after being found in the small gym structure and punished with red ink for who I am as an individual, I transferred out of the Catholic school system. I became ashamed of my sexuality. The experiences with my English Literature teacher scalped my pride like knife against skin, shedding the "sins" my sexuality held in Catholicism. I used to proudly profess my lesbianism - but I became motionless, silent, stagnant. I allowed the identification of “straight” to course through my veins and out of my mouth. I began to lose myself before I began to become myself. Similarly, Hashim describes losing herself in the battle of being Black and being Muslim: the coffee of my skin bitterness of flesh when I try to scratch pain away/ I do not know who I am the longer I allow the sadness to sink in the more I lose myself/ Hashim eloquently uses consonance throughout her poem with the "ssss" sound: "Skin" "Scratch" "Sadness" Sink". This emphasizes her attempts to "scratch pain away" as if she is trying to scratch away the "coffee" of her skin. She feels ashamed and embarrassed by the duality in her identity. Hashim cannot fit into a singular box of "Muslim" or "Black". Her sense of identity fades away as the sadness floods her body. She begins to lose herself as she is stigmatized into a specific label, none of them reading: “Black-idiosyncratic-Muslim-girlchild”. Throughout her book, she teaches us that there is strength in dualities -- even in multiplicities. She ends her poem on an unapologetic note: the problem is staying in this body for a wasteful lifetime The poems in Hashim's new book reveal a society operating like a cage that attempts to trap individuals into a specific box. Hashim's poems offer a counterpoint to society's racism, sexism, and homophobia. She uses these last three lines to make a statement about being the problem vs. fighting the problem. Being the problem is remaining stagnant, much like I did after I transferred from the Catholic school system, but fighting the problem is enacting change. It is not as she explains, "staying in this body for a wasteful lifetime", but using this lifetime to rise up against racism or sexism or homophobia. It took me 2 and a half more years to begin proudly identifying as a lesbian again. I had remained motionless for too long - I was wasting my life pretending to wear the blue Dickie shorts, the black V neck sweater, and the white collared shirt. I became apart of the problem: apart of the homophobia and the discrimination that I myself had experienced. Then something inside me shifted - change, growth, the evolution of self. The more I encountered proud members of the LGBTQ community, the more confidence I gained. I learned to radically accept my sexuality, no matter what anybody else had to say about it. I remained Catholic throughout my entire high school education, I remained Catholic after I began proudly identifying as a lesbian again, and I am still Catholic now. The difference is that now I know I do not need a school or a church or a priest to affirm my faith. I am a Catholic Lesbian proud of being a Woman who loves another Woman. Hashim is a Black Muslim Woman proud of her religion and proud of her race. I believe you -- we -- are enough, whatever we are, and wherever we are.

You can purchase Husnaa Hashim's book and read interviews and watch spoken word videos at her website:

https://www.husnaahashim.com/

Cassie Wilson is the Blog Editor for PCC's Inscape Blog: Instress. She is a current student at Pasadena City College and is majoring in English. She says: "Husnaa Hashim's poetry is important. It is raw and it is real. I found my own perspective in her work, but I want to emphasis the value of her poetry bringing awareness around identifying as a Black Muslim Woman in today's society."

3 Comments

Written by John GenskeIn 2017, I conducted an interview with Marine Cpl. Nathan Kemnitz. Kemnitz, a Texas native, who moved to Pasadena in 2011 and attended Pasadena City College through the veteran's program. This story is based on his life events and experiences as a member of the military: I lay in the dust, broken and splintered and bent, and the sun beat down on my head. The blast picked me up and threw me on my back, knocking the air out of my lungs. The sound from the explosion continued to scream in my ear. I lay there for some time before I could finally form words on my tongue. “Huston! Huston!” I yelled. I couldn’t see anything after the explosion. “Huston!” I yelled once again. He didn’t respond. I could feel the moisture dribbling down my temple. I pressed the pads of my fingers on the warm liquid and then instinctively held my hand to the front of my face, but I still couldn’t see anything so I didn’t know whether it was blood or sweat. I could hear the voice of the corpsman, Dexter, as he and a few others from our company approached. I heard Sergeant Taylor make the call on his radio to get a medevac ready. I sat up on my left knee and used my left arm to support my weight. The right half of my body was not responding to my efforts to move, like it had completely fallen asleep. That was the side of me facing the IED when the blast went off. Dexter tried to talk to me but I paid no attention. I didn’t respond to him, I just kept yelling for Huston. Huston was my best friend. We grew up in the same town, went to the same Lutheran high school, and then enlisted together the day we graduated. His full name was Seth Ryan Huston. He died that day, August 21st, 2004, on a road surrounded by a flat floodplain in Fallujah. Suddenly, I felt my head grow heavy. My neck relaxed and I reclined back into the dirt, staring into the sun. As I faded out of consciousness, I was certain that my death was greeting me. But I did not die. I was sent back to the states. I underwent 25 operations to clean out and reconstruct both my right arm and leg. My right arm was permanently paralyzed and my right leg was severely handicapped. Despite the cataracts that the blast gave me, which caused my initial loss of sight, I regained vision in my left eye. Shrapnel from the IED left my right eye permanently blind. In the following weeks I asked the nurses and doctors about Seth. “He’s doing fine,” they responded each time. I had been in the hospital for a month before Sergeant Taylor came to visit me. I was eager to know about Seth’s whereabouts. “Sergeant, have you visited Seth yet?” I asked him. He paused for a moment, fixing his posture upright. As he drew in a deep breathe, I felt my diaphragm compress around my heart as if he had siphoned the very air from my lungs. “Nathan,” he looked up from his tan combat boots, “when the IED detonated, Seth was practically on top of it. He didn’t have a chance. Even if,” he paused, pursing his lips before resuming, “even if he’d somehow survived, I don’t know the kind of life he’d live. I’m sorry no one told you yet. I guess, no one here wanted you to have to undergo anymore strain.” The hospital room was silent. He stayed standing next to my bed for a while. I stared at my distorted reflection on the rounded aluminum bars of my bed frame. My mind swam in the memories leading up to the explosion. I saw it from every angle, every point of view. I imagined the blast surge from the floor into a mushroom of dirt and debris, swallowing Huston in the blink of an eye. For the next two and a half years I recovered in a Naval Hospital in Maryland. The doctors didn’t know how to prescribe painkillers, so they figured more were better than less. They just wanted to drown out our pain. They made sure we dealt with as little discomfort as possible. During the days we drank ourselves into a haze at the bowling alley. We quarreled with locals and were arrested as often as tracer rounds light up the Al Anbar night sky, though the police always brought us back to the hospital. At night we muddled our minds with the miscellaneous pills and prescriptions that we shared from cot to cot. We traded in our medals for morphine. We numbed our pain with naxolone. We floated in clouds made of oxycodone. We implored these methods to escape our realities; though we all arrived at the same inexorable conclusions. War was a lie. It was no great unifier. It was not glorious. It was a pension and painkillers. The war tried to kill us, and when we were sent home on a stretcher with our loved ones in body bags, the war raised its hand with the rising sun and waved to us goodbye. John Genske is a student at Pasadena City College majoring in Geography. John says: "I draw inspiration from authors like Kevin Powers and Tim O'brien who seek to spread awareness on the horrors of war."

Written by Andrea VazquezPersonally, growing up I had a clear plan of what path I wanted to take: the path of having an education, success, happiness, and clarity. “All Roads Lead To You” by Donald Cauble focuses on the diverse paths people end up on. Cauble explains that one path can lead to any road wanted. The choice is theirs and it depends on where their heart and motivation is at. Unfortunately, that is not always the case, certain uncontrollable events occur and we get a bit lost sometimes. Thanks to these big plans of hopes and dreams, some people have an idea of where they will end up in life. However, some people have no clue and just play it by ear and that is okay too. Cauble says, But for those who treasure love in their hearts, no matter what-all roads lead to you. Cauble’s words are the reality to our society, we are the ones who choose our paths by our actions. Sometimes we end up in places we didn’t choose, but these are, which lead us to the unknown. However, we always have a choice. It all depends on the person, their environment, and their ambition towards their passions. My life path resonates with Cauble’s words. Growing up my parents always had my best interests at heart, while guiding me. However, as the years went by my interests began to change. Uncontrollable events occurred that affected my choices and thinking. The choices we make are influenced by the people around us, the interests we like and what we are being taught. This is why it is important to be aware of what and who we are being exposed to. I enjoy the fact Cauble mentioned the variety of people and paths in life. He states, For some, no doubt, to fame and fortune. For some, to drugs, taverns, a life of crime. For many, a life serving the needs of others. He mentions a few of the typical lives; people being famous in the entertainment industry while others end up abusing drugs and falling into alcoholism. This made me wonder and reflect on my current life in comparison to my old plans and goals. I realized I am where I am because of the people I surrounded myself with and that fear made me incapable of creating changes to my life. I always surrounded myself with people who were ambitious about their education and being successful, however, while my darkest thought consumed my soul I began to surround myself with people who were adventurous, wild, and free in being themselves. These people taught me it wasn’t just about being successful and having an identity accustomed to society. It is up to the individual to create the change one wants to see. I have hope for my own future and I refuse to give up on the goals I have planned, even if things don’t go as planned. Life is full of unexpected possibilities and I’ll end up on the designated path created for me. Caudle's message may be perceived in different ways, some say it’s about love and others believe it’s about how our lives turn out to be. Andrea is currently a Pasadena City College student majoring in Graphic Design. She not only enjoys designing but also enjoys fashion, photography, and music. She says, “ Our faith doesn’t determine who we are, we create ourselves.”

Written by Cassie Wilson

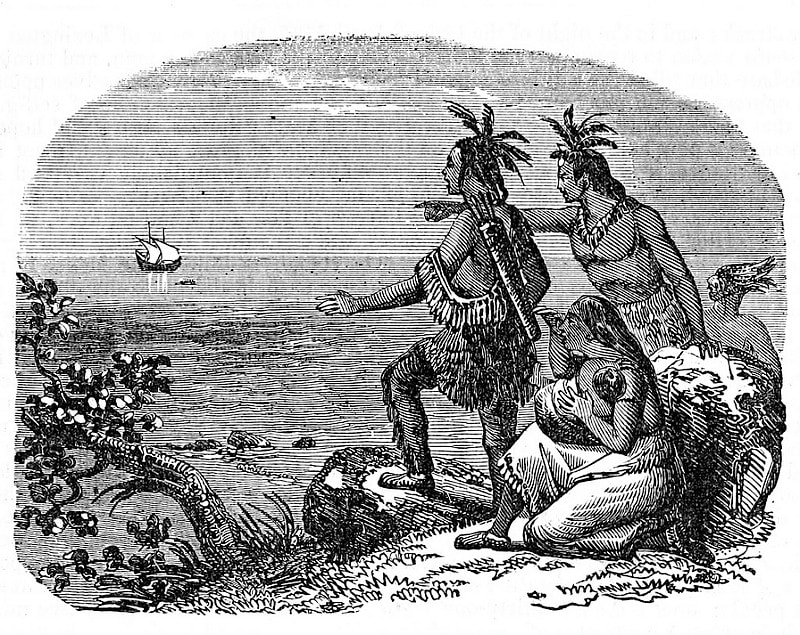

When the sun rises this morning and the coyotes and jackrabbits that occupy this land awake from their slumber, people will joyfully jump from their beds. Some families will scurry in their cars, fasten their seat belts, and head to their neighborhood church. Hear sermons, take communion, and feel blessed by their faith. While others will greet the members of their family around the kitchen table - happily anticipating the day’s festive activities.

Throughout the day, at no set time, people will honor the pilgrims who set sail to the “New World” - that was taken from its indigeneity - and give "thanks" for the thousands of Native Americans who gave up their homes, lives, culture, and humanity. Little ones dressed up in Indigenous themed construction paper cut out’s will yell, ”Happy Thanksgiving!” unaware of the falsehood this holiday really holds. Jonathan Garfield’s poem, “Thanksgiving” echoes the native truths of this holiday in America. Garfield is a Native American poet and apart of the Fort Peck Assiniboine and Sioux reservation located in Montana. Jonathan is one of the thousands of Native individuals who have been affected by American colonization. The tragedies of his people and a myriad of other tribes is illustrated throughout his poem: Thank you for relocating relations, relocating their hearts, some forgetting or ashamed of their Indigenous roots. / Thank you for Catholic boarding school surgeons painfully removing our Native tongue without anesthetic until our mouths bled English. / Thank you for stealing our land, raping it like some woman you never knew the name of, leaving her crying, traumatized, bleeding. When the pilgrims set foot on the soil of the New World it was for their freedom from New England religious control. They embarked on their journey so that they could live a life of religious freedom. Except during this freedom exhibition, they tore the roots of Native Americans lives from their land. The military controlled Indigenous life, they relocated tribes into “boarding schools” or “reservations” where they were beaten, killed, whipped, silenced, and Americanized. Their culture was condemned, they were not allowed to practice their sacred dances, speak their own language, or believe in their own religion. They were prisoners of somebody else's freedom. As time paced on and America molded itself into a democracy, the allusion that Indigenous suffering was over - begun. Garfield continues to describe the suffering that Native souls still endure today: Thank you for alcohol that now courses like blood through reservation veins. / Thank you for the reservation suicides that have killed the spirits of those left behind. Alcoholism, substance abuse, domestic violence, depression, self-destructive behavior, suicide ideation, feelings of shame and unworthiness are all symptoms of present and past Native American life. The massacre of Indigenous life and the suffering endured in the “reservations” courses through Native American veins. Historical Generational Trauma is defined by psychologists as the collective wounding of an individual or generation from a severely traumatic event. Like a ripple effect, the harsh abuse that the Natives on the “reservations” experienced was transmitted generation to generation. Indigenous mothers and fathers began to treat their children how they were treated by the Americans. The symptoms above began to manifest themselves - symptoms of the tragedies of lost lives, tradition, culture, and basic humanity. So, today as families gather around their tables in ignorant bliss and the abundance of food is warmly served into the mouths of individuals who never knew the scent of blood beaten skin, the prisoners of freedom will be remembered. Their suffering will be not be silenced, their culture will not be shunned, their indigeneity will not be taken from them. In order for healing of past traumas to began for the Native Americans - the awareness of the genocide of their people needs to be present. Today thousands of silences will be held in honor of the compassion, the generosity, the kindness, the selflessness of the Native Americans who shared their food with the pilgrims on this Thanksgiving day hundreds of years ago. It is their humanity that allowed the pilgrims to live and America to flourish.

To read Jonathan Garfield's poem, "Thanksgiving" please visit the link below:

https://newsmaven.io/indiancountrytoday/archive/thanksgiving-a-poem-by-jonathan-garfield-hHK2ksuqskKKLO8spK8SSw/

Cassie Wilson is a student majoring in English at Pasadena City College. She says, "The history of America that is taught in the education system often lacks the Native American genocide. This tragedy is an important event in history - it should not be silenced or forgotten. Native life is present, their trauma and loss is immense. In writing this blog post I am in no way trying to persuade individuals to not celebrate Thanksgiving, but rather to honor the thousands of lives lost during the colonization of America during the holiday. Healing is possible for Indigenous people and in order for that to occur, the awareness of their suffering should be present during Thanksgiving."

By Andrew Zapata

Poetry is a form of art, and this form of art offers everyone a platform to express themselves and to affirm their own voices. For me, my fascination with poetry began in an unlikely way. I was 18 when I started my first semester at Pasadena City College. At the time I had no intention of pursuing an academic degree, but I couldn’t let my parents know that. I always romanticized becoming a working-class dude with a blue collar job: a simple life. Wrenching on cars sounded awesome and so when I hit PCC that Fall, the only class I took was Auto 32.

My plan to ignore the more academic classes in favor of the hands-on classes was going great, but then it came time to register for another semester, and while I wasn't sure what I would take, my parents had no problem demanding that I sit down with them to make a full, educational plan for transfer to a 4-year degree. I was forced to pick what my mom called a "more serious" major. I had always enjoyed reading and writing, so I picked English. I found writing pretty enjoyable but also, I think I had some romanticized notions of being an English teacher. I had been madly in love with my high school English teacher and even went as far as asking her out! It goes without saying, we never made off into the sunset, but maybe English was still for me. After a few semesters, I landed in ENG 53 - Poetry, with Dr. Kirsten Ogden. I had always thought my own words might count for something, and in this class, I was introduced to the intimate science of poetry and the voices of so many others. One poet that I found particularly relatable turned out to be Zubair Ahmed, author of City of Rivers. I discovered in the online article “The poetics of home with Zubair Ahmed” that he and his family came to America to escape the political instability and poverty of Dhaka, Bangladesh. He was a child when they won the Diversity Visa Lottery and were granted green card access into the country. Ahmed describes Dhaka as a densely packed city to the point where he states, “When you walk down the street [in Dhaka], you breathe the breath of the person standing next to you”. I found his comment relatable as a Los Angeles native. This city has an estimated population of four-million people, I sometimes feel a similar invasion of space living here. One poem in particular that I love by Ahmed is "The Water of Lake Tahoe". Ahmed opens his poem by painting a wonderful feeling of Nirvana-like bliss. The sound of water repairs my skin. I stand inside the wind, Breathing in the tips of waves And the branches coated In pre-dawn ice. I share Ahmed’s appreciation with nature through my own love affair with poetry and mother nature. A tranquil effect coats the senses from the sound of moving water, the feel of a wind’s embrace, and breathing crisp air that only exists in the early hours of the morning forest. It is very easy to forget the therapeutic healing nature can offer, especially for those of us in the city. Like Ahmed, I too find peace and serenity when I’m outside alone. There is nothing better than having a quiet space and time away from the pollution of everyday life. Having the freedom of clear un-encroached thought is an inexplicably delightful gift from nature. The rest of this poem takes a polar opposite sentiment. The final seven lines read: I’m afraid to go anywhere. I’m afraid of the empty rooms That await me, The photos on my table That must be sorted. The heaps of paper being folded By the ghosts who refuse to haunt me. The physical world’s natural beauty is life’s man-made horror. Ahmed explains, “I’m afraid to go anywhere”. There is a sense of fear within him that relates to the confines of to the confines of 21st-century life. The rest of the poem’s tone shifts from soulful freedom to lingering thoughts of enslavement via tasks and objectives; existing only from a dominant culture of modern technological advancement of just a few centuries. Ahmed expresses fear that is all too real and relatable for anyone who’s exposed to living in Western culture/society. Life becomes synchronized and monotonous when it’s dependent on working, creating an ominous cycle of working to live and living to work. I realized that my former aspiration of becoming a labouring mechanic, clocking in and clocking out, isn’t for me. Ahmed captures the culture clash between Western vs. Eastern values. He is an Indian born Native which means he is apart of a culturally Eastern sensibility. This is represented in the first half of his poem, as nature plays a very influential role in his part of the world. The second half of the poem represents symptoms that are well known to Western culture because work and worry are unfortunately synonymous with each other. Western society values work and mutes holistic views on life. Eastern society, on the other hand, values a more holistic approach to life over a rat race mentality. In retrospect, I don’t blame myself for just wanting to start my life without an education. Like Ahmed, I find myself contemplating a life without man-made horrors. We both have an appreciation for holistic ways of healing and find our distinct voice in nature. Poetry has molded me into a more whole individual, defining my voice and perspective on life. I am so happy that I found that English 53 class with Doctor Ogden; without it, I might still have been that adolescent boy with dreams of being a day laborer.

Andrew is a student attending Pasadena City College. He says: "My admiration for the written word serve as influences to pursue an academic career in English."

To read more of Zubair Ahmed's work please visit:

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/zubair-ahmed

|

IMPORTANT NOTE:

PCC Inscape Magazine, housed at Pasadena City College, is following Coronavirus protocols. At this time our staff continues to read submissions and publish web content. Note:

Blog Posts reflect the opinions of the writer and not the opinions of Pasadena City College or Inscape Magazine Editorial Staff Members. Archives

December 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed