- Folio No. 9

- About

- Feral Parrot : The Blog

- INTERVIEWS

- SUBMISSIONS

-

ISSUE ARCHIVE

- PRINT Chapbook No.6 Healing Arts

- Online Issue No.9

- Online Issue No.1 Fall 2016

- Online Issue No.2 Spring 2017

- ONLINE Issue No.3 Fall 2017

- PRINT Vol 72 No 2 Fall 2017

- PRINT Vol 73 No.1 Fall 2018

- ONLINE Issue No. 4 Fall 2018

- Online Issue No.5 Summer 2018

- FOLIO No.1 Fall 2018 VOTE

- ONLINE Issue No.6 Fall 2018 Fall Spirituality

- FOLIO 2 Fall 2019 Celebrating Dia De Los Muertos

- FOLIO No.3 -- Moon Moon Spring 2019

- FOLIO No.4 Celebrating New PCC Writers

- FOLIO No.5 City of Redemption

- FOLIO No.6 Spring 2020

- FOLIO No. 7 - Winter 2021 Into the Forest

- 2022 Handley Awards

- Inscape Alumni Board

- PRINT Chapbook No. 7 Healing Arts

- Blog

- Untitled

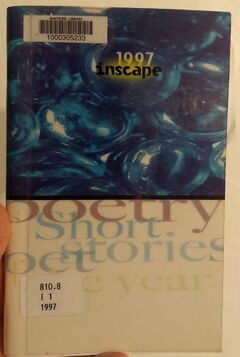

Written by Kaylin Tran Photo by Kaylin Tran Photo by Kaylin Tran Rows upon rows of old Inscape issues line the library shelves like a treasure chest waiting to be discovered. Some pieces date back to the 1940s--yet all of them hold a timeless quality that makes them relevant today. Formerly known as Pipes of Pan, these issues contain stories, poems, essays, and artwork created by students of PCC. The 1997 copy of Inscape first caught my eye with its vibrant blue cover. Although the external design is loud, delving deeper into its pages reveals a surprisingly clean, minimalist aesthetic. Multiple pieces sometimes occupy one page, but the layout allows enough room so that it doesn’t crowd the space. Instead, it feels like a smooth transition from one piece to the next. Simple black-and-white artwork decorates the pages sporadically but with intention; some are large photographs while others are tiny silhouette figures at the bottom corners of the pages.  Photo by Kaylin Tran Photo by Kaylin Tran Interestingly, a page full page of haikus is placed in the middle of this issue. The works are printed against a background of artwork that certainly makes it stand out from the rest of the plain white pages. If someone were quickly flipping through the book to look at everything in a glance, this would be the first thing to catch their eye. Additionally, haikus are short by nature, so formatting them in this manner adds a level of intrigue and allows for a greater appreciation of them. Suzanne Faust, like many of the other writers included in this anthology, included multiple works, but her short story “Secret” resonated with me in particular. I’m unsure if the magazine’s mission statement from 1997 is similar to our current motto of including the “unique inner nature of everything and every person,” but it certainly does manage to capture Inscape’s current branding in a riveting yet incredibly unnerving manner. “Secret” is about a 12-year-old girl innocently discovering her emerging sexuality, which is completely normal for a person her age. However, she explores this with older men--construction workers who smile at her as she makes her way to school everyday. One young man in particular approaches her and asks to meet her later that day. Although his “legs [were] casually relaxed, his eyes hidden, smoking a cigarette while [she] would walk towards him,” Faust subtly foreshadows the man’s malicious intent by describing his body language as “intent, tight, regardless of his informal pose.” The innocent girl juxtaposes the sinister man even further when it is mentioned that her leather school backpack bounces off her back as she runs away, too fearful yet excited to speak to him. They meet again later that day as agreed. However, there is an immediate turn in the plot. When she arrives, they simply stand at a distance and stare at each other until he breaks their long stretch of silence by saying “Go away. I can’t do this to you.” As the girl runs away, both her and the reader are left with breathless, immediate relief as the man lets her escape untouched--unscathed. Faust ends with an insight into the girl’s only thought: “Never again would I experience the same complete power of seduction or escape totally unharmed when desire was about to open its self-indulgent, reckless mouth.” “Secret” completely encompasses aspects of the unique inner nature of people, from the human, to the becoming, and the unexpected. As beautiful it is to see a young girl growing and emerging into adulthood, seeing her innocence nearly marred by the corrupted nature of the construction worker reminds us about harsh truths that exist in reality. The human aspect in every person references to people’s strengths and flaws, to their good and bad thoughts, to the innocent and corrupted. Faust’s short story is an excellent interpretation of this. Not all of the following works in this issue match the dramatic emotional complexity of “Secret,” but each one tells a story about common human experiences. Other examples are Susan Dimos’ “Point of View,” a short story from the perspective of a homeless woman; Mandi Bartell's “Good Morning Love,” a poem about a person’s romanticized dream of a loved one; Jason Chen’s “Oxford Tea,” a poem in which the speaker reminisces about treasured memories with good company in the face of loneliness. The archives section of the library contains a trove of older Inscape issues ready to be discovered and well-loved. It’s interesting to see the shift in style, tone, and design as each edition changes throughout the duration of the publication’s existence. The 1963 issue is a text-heavy edition filled with works that are more imaginative and fictional; the 1984 issue has shorter pieces that are more realistic, as if they're actual experiences from genuine people, that are intertwined with large silhouette and outlined artwork; the 2001 issue is by far the more experimental and creative edition with its spiral-bound cover and detachable postcard artwork. Writers like Faust demonstrate the gifted literary skills that PCC-affiliated students possess. Most others who submit their works aren’t professional writers; they’re simply students who possess a shared appreciation for all things creative. This is what Inscape strives to represent in each of its publications, and what it will hopefully be able to continue to do in the coming years. Kaylin Tran is a writer who hopes to make her hobby a reality by working in the journalism field. She says "Writing factual, formulaic pieces is an aspect that I love about journalism, but something about reading and analyzing creative works is more satisfying. There's no better feeling than when you've successfully dissected a piece filled with hidden meanings."

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

IMPORTANT NOTE:

PCC Inscape Magazine, housed at Pasadena City College, is following Coronavirus protocols. At this time our staff continues to read submissions and publish web content. Note:

Blog Posts reflect the opinions of the writer and not the opinions of Pasadena City College or Inscape Magazine Editorial Staff Members. Archives

December 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed