- Folio No. 9

- About

- Feral Parrot : The Blog

- INTERVIEWS

- SUBMISSIONS

-

ISSUE ARCHIVE

- PRINT Chapbook No.6 Healing Arts

- Online Issue No.9

- Online Issue No.1 Fall 2016

- Online Issue No.2 Spring 2017

- ONLINE Issue No.3 Fall 2017

- PRINT Vol 72 No 2 Fall 2017

- PRINT Vol 73 No.1 Fall 2018

- ONLINE Issue No. 4 Fall 2018

- Online Issue No.5 Summer 2018

- FOLIO No.1 Fall 2018 VOTE

- ONLINE Issue No.6 Fall 2018 Fall Spirituality

- FOLIO 2 Fall 2019 Celebrating Dia De Los Muertos

- FOLIO No.3 -- Moon Moon Spring 2019

- FOLIO No.4 Celebrating New PCC Writers

- FOLIO No.5 City of Redemption

- FOLIO No.6 Spring 2020

- FOLIO No. 7 - Winter 2021 Into the Forest

- 2022 Handley Awards

- Inscape Alumni Board

- PRINT Chapbook No. 7 Healing Arts

- Blog

- Untitled

Written by Cassie Wilson

I walk through the doors of the green and grey Starbucks building exactly 4 miles away from my house. The barista asks me what I want. “Venti, hot, soy, peppermint mocha please", I somewhat stutter. We exchange nonchalant expressions as I hand the money to him. 10 minutes later, I’m sitting down, coffee beside me, a book in my hands: City of Rivers by Zubair Ahmed. I’m completely unaware of the voices echoing around me; the many conversations happening at the same shared table I occupy. Too engrossed with the work I don’t even hear my name called as I read an excerpt from the poem, 4 A.M:

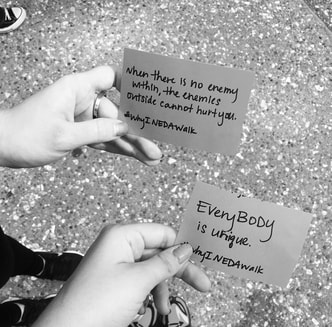

You go outside, Place your body Deep inside the darkness And wait for snow/ I imagine Zubair Ahmed, Bengali immigrant, his life rich in culture and tradition. His poetry filled with the experiences that shaped how he perceives the world. Ahmed describes an individual going outside in the “darkness” waiting for the snow. I begin to remember a time in my life where I placed myself in my own darkness. A time where I waited for the snow. Where I was so deep inside my own self-destructive nature that I just expected my downfall. Throughout my life my perspective has had many renovation processes. I’ve been carved out, filled up, carved out again and then left to pick up the pieces. The most prevalent life experience that has shaped how I perceive the world would have to be the 60 days I spent at the Bella Vita facility in Pasadena, CA. I remember my first day. The giant red brick building that sat in front of me. It looked obscure and uninviting. Every inch of myself was telling me to turn around, drive back home and never look back. I puffed the last of my cigarette as I sat outside the building. I was hoping that some natural disaster happened in front of me. Anything to stop me from entering and talking about the unspeakable. I put the cigarette out, wiped the tears from my face, and entered the giant red brick building. Most of the time somebody hears the word “eating disorder” and a picture of a tiny boned, fragile framed girl comes to mind. This was not the case for me, nor is this stereotype even remotely true. I was an overweight 19 year old when I first stepped inside the giant red brick building that made up the eating disorder facility that soon became my safe haven. A myriad of emotions flooded my body. I was scared, ashamed, and mostly pissed off. I did not believe I needed to be there. I missed my intake appointment the day prior and the facility called my mother. My god damn mother. I was past the point of annoyance. I wanted to scream: I DON’T NEED YOUR HELP! I spent the hour prior to my appointment driving down the street from my house, turning around, coming back home, and then leaving again, finally arriving into the grey small parking lot of the facility. Then, sitting in my car chain smoking cigarettes, while balling my eyes out. I did not want to do this, but something small inside me told me I had to try. During my intake appointment I barely remember all the questions they asked me. I tried to focus but the surging pain of acid embodied my teeth, throat, and tongue. The words “bulimic” stung me to my core. They explained their treatment plan to me, but I wasn’t listening. I was planning and preparing for what I was about to endure. See, the thing about someone with an eating disorder is that control is the only thing that matters. My mind was obsessed with numbers: my weight, the calories I would intake throughout the day, the amounts of chews I took, and how many pounds I could lose. Much like Ahmed, everything in my life was routine. He illustrates in his poem: I Watch The Shadows of Birds Waking at Dawn to Pick the Worms Clean: I know what the day holds-- Organizing bottles of fish oil on my shelves, Feeding the spiders in my keyhole three poppy seeds,/ Children gather at the bus stops, their faces covered with black boxes. /the students line up with their white shirts and khaki pants Ready to write about the secret lives of sparrows. /I will wait till night falls and I can’t see The shadows of birds surrounding me. Ahmed's life in Bangladesh was a fixed program. His culture spilled out in his day to day experiences. When he illustrates himself waiting until “night falls”, he is waiting for his moment of freedom. Similarly, I had felt prisoner to my surroundings. I knew exactly what my day would consist of: restricting, binging or purging. Ahmed felt trapped in his culture, just as I felt trapped in my eating disorder. I remember the intake was over before I even begun listening. All I knew was I would spend everyday in the facility from 10AM until 7PM, having every meal and snack there. FUCK was the only word I remember thinking of. After my first week at the facility I recall wanting to desperately leave. My thoughts ran marathons in my head: Who are these people? Why am I here? Why should I trust them? I was resistant, cold, and unresponsive. The first meal I had with the group was terrifying. The diet tech observing the group explained to me that if I did not finish the food on my plate, I would have to drink an Ensure. It was a chocolate, chalky liquid that served as a meal replacement. The girl sitting next to me looked me dead in the eyes shaking her head. She leaned over and whispered, “You should eat the food. The Ensure is twice the amount of calories that your food is. So, it’s better to force feed yourself the meal.” I ate every meal the entire 60 days I was there. Week two my personal therapist asked me who I was. Those words confused me. I knew my age, my weight, the color of my skin, hair, and eyes. I knew where I went to school, what city I grew up in. I told her all of the above. She smiled and said, "Who you are is not where you are from or what you look like. I want to know your goals, values, and beliefs. That is who you are." That was the first time I realized how lost I was. In the poem, I Close My Eyes and Find Myself in the Exact Center of Dhakra, Ahmed feels that same confusion of identity. He explains, Tell me why the sky is above And not under our bodies. /The world becomes transparent. I don’t understand anything anymore-- The moon walking away from us Because we’re discovering Who we really are/ Ahmed is slowly figuring out who he is and what it means to be a Bengali. He reminisces about the discoveries of his people and feels confused and lost. Just as I felt lost in this hour long therapy session of what if’s and who’s who. Ahmed and I shared a common goal: uncovering our true identities. The third week I ached to be out of my body. Part Two is scheduled to post on Wednesday, October 17, 2018. Stay Tuned!

If you want to read Ahmed's work please visit:

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/zubair-ahmed

Cassie Wilson is from Burbank, California. She has a passion for poetry and a unrelenting love of writing. She is currently attending Pasadena City College, majoring in English. Cassie says, "my journal is my best friend and my pen my partner in crime."

1 Comment

Vanessa

10/18/2018 10:20:41 am

Your story and words are deeply inspiring and I hope that one day they reach enough people to change the view on our bodies as women.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

IMPORTANT NOTE:

PCC Inscape Magazine, housed at Pasadena City College, is following Coronavirus protocols. At this time our staff continues to read submissions and publish web content. Note:

Blog Posts reflect the opinions of the writer and not the opinions of Pasadena City College or Inscape Magazine Editorial Staff Members. Archives

December 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed